FIELD NOTES BLOG

Exploring the Four Rivers of the Rockford Area

Over 3 Trillion gallons of water falls in the Illinois Rock River Basin (that’s the Northwestern portion of Illinois) and that water has to go somewhere! Four rivers pick up the slack and carry the water through Winnebago county. I’d like to introduce you to the story of each river and offer some of the best places to visit if you are trying to enjoy everything they have to offer!

Meet the Rock River Watershed

A watershed is an area of land that channels rainfall and snowmelt through streams of water to a unifying body of water. The Illinois portion of the Rock River watershed covers about 5,650 square miles worth of land. The entire watershed is called the Rock River Basin and its about 10,915 square miles including parts of Wisconsin as well as much farther Southwest of Rockford towards the Quad Cities and the Mississippi River. Winnebago County boasts three rivers that flow into the Rock River, making up a portion of the Rock River Watershed.

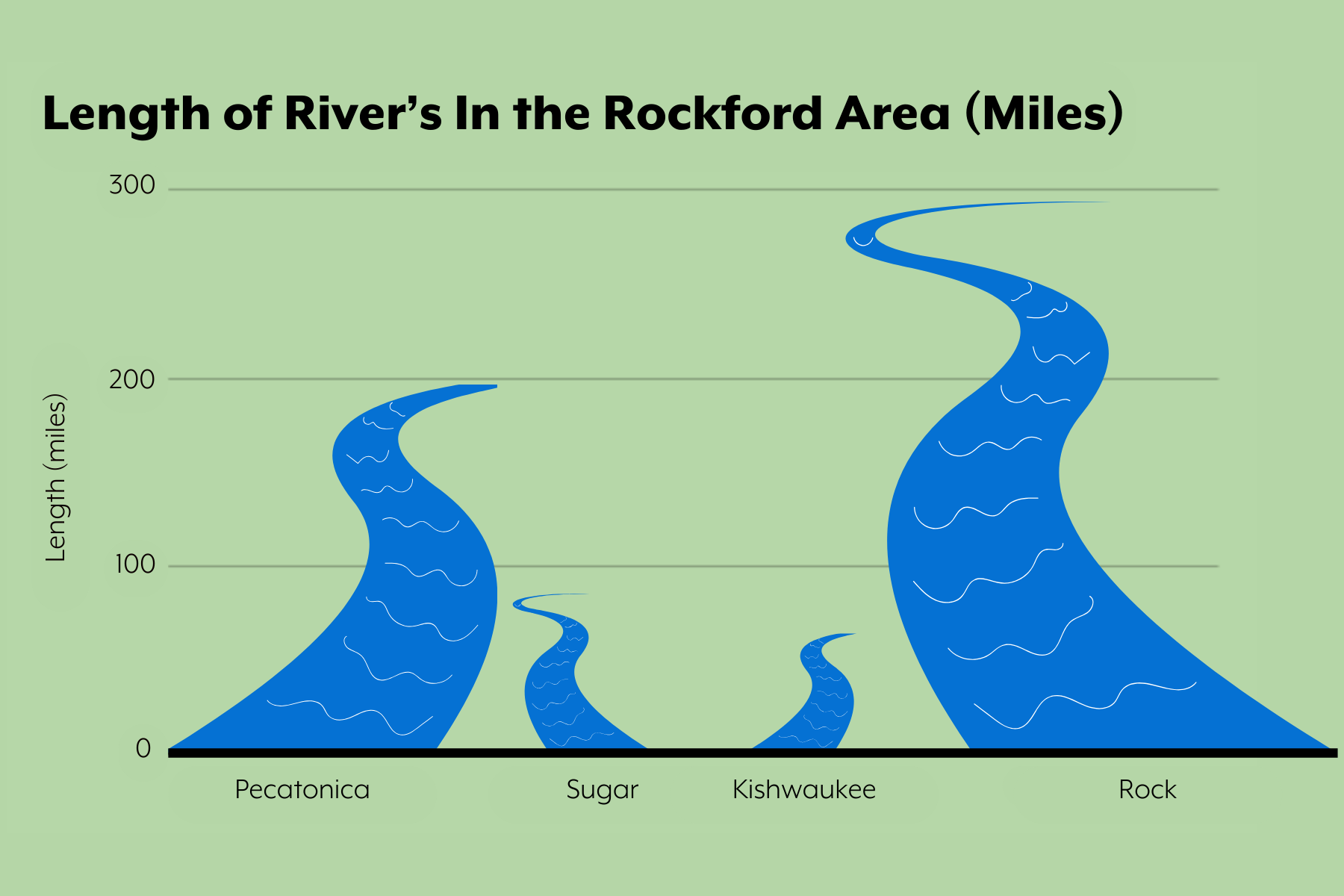

We will start with the shortest river at only 63.4 miles (102 km) long: the Kishwaukee River. It is a lovely river that is teeming with wildlife around every bend. Next, we have the Sugar River! This wild and winding river stretches out to be 91 miles (146km) long. This river is a tributary (meaning it’s water flows into another river) for the Pecatonica River, which coincidentally is our next river running at 194 miles (312 km) long. It is a peaceful length of water with a slow meandering current. Lastly, we have the Rock River which all of the water from each of the rivers will eventually flow into. This urbanized river is a heartbeat of the watershed and it has been useful for many years by plenty of people. The Rock is a whopping 299 miles (481km) long and will eventually flow into the Mississippi River.

Ancient Rivers

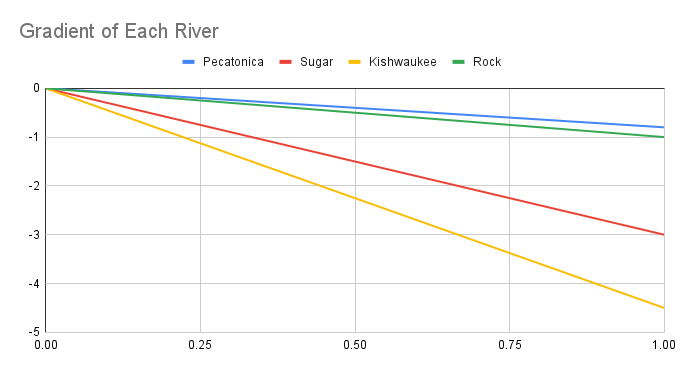

The simplest way of tracking the age of a river is to track the gradient that the water is traveling on! The gradient of a river is the measure of how steeply it loses height. A river with a high gradient loses height quickly, has a stronger current, and is relatively younger. A river with a gentle gradient loses less height and is typically a slow-flowing, mature river. Some streams have such a gentle gradient that they aren’t measurable without special equipment. Here are the gradient rates for our Rockford rivers.

- Kishwaukee: 3-6 ft/mile

- Sugar: 3.0 ft/mile

- Pecatonica: less than 1 ft/mile

- Rock: 1 ft/mile

Here it is also visualized!

With just this one trait alone we can tell a lot about each of these rivers. The Kishwaukee and Sugar Rivers are relatively young, which is reflected in their gradient. The Rock and the Pecatonica both are probably older, more settled in. The figure representing the gradient of each river shows how much on average the river changes in feet over 1 mile. It also shows how much steeper the Sugar and Kishwaukee are compared to the Pecatonica and the Rock River.

Let's get a little bit more specific. We can track the age of a river on the geologic time scale as well! The rivers in this area can’t be older than 323 million years old because, back then, Illinois used to be a shallow sea of tropical warm water. Last I checked, rivers don’t flow under the sea (small red crab begins to sing). More recently, our landscape was covered by a few sets of massive glaciers traveling through Illinois. They existed between 300,000 and 130,000 years ago during the Illinoian glacial period. Shockingly, the Rock River was around at this period, and it used to connect to the Illinois River. It was heavily altered by the glaciers leaving behind loose rocks carried all the way from Canada! These Canadian Rocks blocked that path and pushed it towards its modern day streambed that might be more familiar to us on a map. That means on its current path the Rock River is about 130,000 years old but its older paths would put it easily into the millions of years old!

On the other end, the Kishwaukee is extremely young (for a river). It was made by glacial meltwash around 13,000 years ago and thus had not had much time to erode away at the slope that it flows along. We can tell it's on the newer side given the immense amount of diverse and unique rock that was brought from much farther north and deposited on top of the remains of the older glaciation periods. This data also confirms why the gradient of the Kishwaukee is so much steeper than the Rock River.

Best Places to Enjoy Each River and the Ecology that makes it so Wonderful

These rivers flowing together are essential for the ecology of the land with many interesting flora and fauna to find and enjoy! They act as a legacy piece of the last glaciation periods. All of these ecosystems are explorable too! Let me tell you about some of the best places to visit if you want to enjoy the rivers.

Rock River

This river is near and dear to my heart given I have lived right next to it my whole life. It is a constant source of support for everything around it, taking all the water from the other 3 streams and many more as it travels farther south. It is well known for its rocky waters (given that’s how it got its name) and the base is largely bedrock but has massive swaths of gravel along it and smaller segments with mud and silt. It averages a depth of 15 feet deep but at some points can get to 50 feet! The Rock is the biggest river of this group therefore I have the most suggestions for you to check out and explore for yourself!

The Cedar Cliff Forest Preserve is a magnificent preserve being actively restored into a shortgrass prairie.These efforts demonstrate the desire we have to improve and repair the land that has been essential for our continued existence. This preserve also hosts a mesic forest, its namesake of this area: massive limestone cliffs extending 800 feet along the Rock River. Here you can find wonderful woodland wildflowers. Some of these flowers include the Wild geranium, Red trillium, and Bloodroot along with a canopy of Bur, Red oaks, and a rare species of oak called the Chinkapin. These cliffs act as a unique habitat that supports diverse plant communities and give you an impressive view of the Rock River.

The next preserve to explore and enjoy is the J. Norman Jensen Forest Preserve with a beautiful spot by the dam to experience. Within it is one of the rarest prairies out there :a remnant dry gravel prairie hosting a rare ecosystem.

The Macktown Forest Preserve is also a beautiful spot along the Rock River. Macktown holds the confluence point of the Pecatonica and the Rock Rivers. It features a golf course and historic settlement. Macktown Living History, a non-profit friend of the Forest Preserves of Winnebago County, hosts programs dedicated to teaching about the people who have lived throughout the area.

Sugar River

Not much of the Sugar River flows into Illinois before it joins into the Pecatonica (only about 5 miles of its 91 mile stretch) but that doesn’t mean it's not an important aspect of Illinois. It's a clean river flush with trees and vegetation. The Sugar River Forest Preserve is 529 acres and helps accentuate the Sugar River’s wild and secluded nature along with the ability to experience it for yourself. The trails are serene and there are a variety of activities you can do! I really enjoy the camping spots which you can set up right along the winding river and its array of wetland animals. Sugar River is also a fun stream to take trips down on for paddlers and tubers alike.

Pecatonica River

The Pecatonica. A name originating from two Algonquian languages meaning Slow Water. It follows along a very crooked, slow moving channel that doubles back on itself regularly. Its soil bed is mainly sandy loam. The best place to experience this river is at the Pecatonica River Forest Preserve. Here is one must-stop place if you are trying to enjoy what our rivers around here have to offer. Along the border of this park is the slow meandering Pecatonica an ideal representation of a kind old river. Its water travels by at a relaxing pace. This park is 466-acres of woodlands and oxbow swamps with 2 major segments (the lower and upper parts). Some of the best places to enjoy the water are right off the peninsula past the lower parking lot where you can get very close to the water. The upper area has an observation deck that can give you a wide view point to enjoy all the beauty the Pecatonica has to offer. The oxbow lakes also act as living history showing how long the Pecatonica has been around. Oxbow lakes form in older rivers when a river cuts through a meander neck causing the old channel to be skipped for the more immediate channel.

Kishwaukee River

The Kishwaukee name originally comes from a Potawatomi word and it means the River of the Sycamore. They would use the large Sycamore trees nearby to make canoes and travel along the river with them.

If you had to pick one river to explore, I would personally suggest this one. Find a way to paddle or float down the Kishwaukee to really enjoy so much it has to offer. The Kishwaukee is one of the highest quality streams in Illinois with extremely clean water and a diverse ecosystem it supports. My favorite way to enjoy the Kishwaukee River is taking a kayak along its water and just breathing in all it has to offer. The water is a fun challenge of winding turns and fast straightaways. The plants and animals also always give you a new thing to look at. It's a generous river that holds so much potential for enjoyment and exploration. To quote a good friend here at Severson ‘Its almost like the Kishwaukee wants to be explored’ because of the amazing things it shows off regularly to its guests.

The best place to enjoy the Kishwaukee is at the Kishwaukee River Forest Preserve. The mature forests act as good places for migrating birds to rest and Smallmouth bass are famously common here, so if you are a fisher or a birder you are sure to enjoy it. I would check out the stone Fort Vicennes and the two bridges which were built back in 1934 to really feel a sense of wonder to the history that exists around you.

Explore and Enjoy the Rivers!

All in all there is a lot to learn about and experience with these rivers. The history of the region is ripe with knowledge and I barely scratched the surface about all we know about these rivers. What’s more important is to explore the rivers yourself. Go out there! Play in the water, travel the trails, spot some birds, and make sure to leave no trace so that everyone has the opportunity to experience these rivers for the first time!

RECENT ARTICLES