FIELD NOTES BLOG

World Population Day

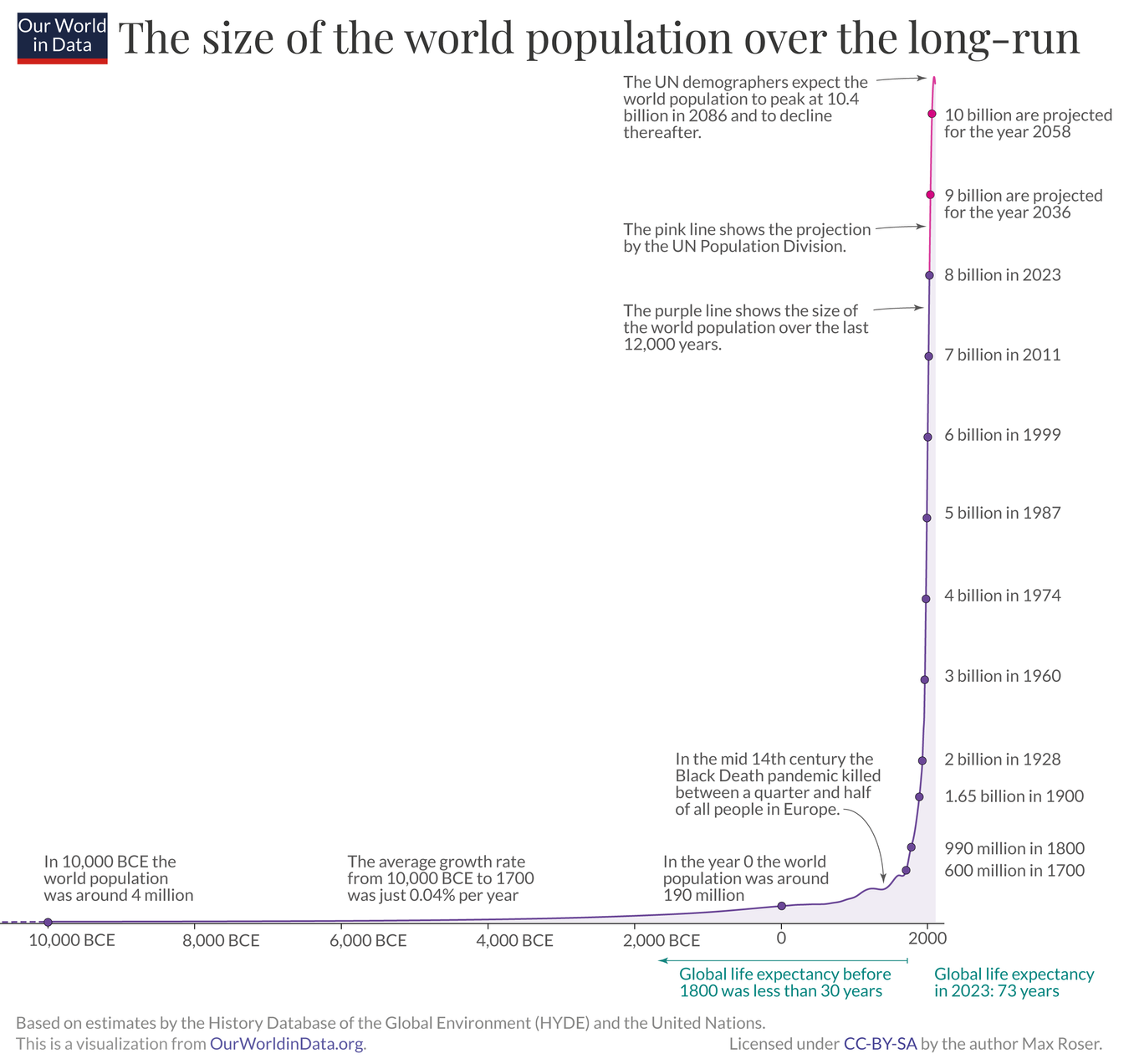

On July 11, 1987, the global population reached 5 billion people, an event commemorated as the Day of 5 Billion. This milestone led to the establishment of World Population Day by the United Nations to raise awareness of the urgency of global population issues. Every year on July 11, we observe this day to reflect on population growth and its implications. Today, the world population exceeds 8 billion, which is nearly double what it was when World Population Day first began. World population can be a difficult topic to broach, so in honor of World Population Day, we are going to discuss the causes and effects of overpopulation, and their underlying presumptions for the future.

It took hundreds of thousands of years for the world population to grow to 1 billion, but only about 200 years to increase more than sevenfold. In 2010, the global population hit 7 billion, and it stands at 8.1 billion today. According to current UN projections, our population is expected to grow to 9 billion in 2037, and to 10 billion in 2058. The world population doubled from 3 billion in 1959 to 6 billion in 1999 and is estimated to increase by 50% over the next 40 years, reaching 9 billion by 2037. This exponential growth is staggering and incredibly hard to grasp. To put it in perspective, the current global population of 8.1 billion represents nearly 7% of all people who have ever lived on Earth. Simply stated, our population is growing too large and too quickly, putting us beyond Earth's sustainable means.

Overpopulation refers to a situation in which the Earth cannot regenerate the resources used by the world’s population each year. Experts say this has been the case every year since 1970 (the population then was ~3.7 billion), with each successive year becoming more and more damaging. Claiming that we are facing an overpopulation crisis is not hyperbolic, as our state of overpopulation is an indisputable fact. However, the conversation on overpopulation can become controversial and problematic when the question of who is responsible for, and what should be done about, the issue is broached. This question should under no circumstance be used as the framework to suggest that certain groups of people are to blame for the issue, and that certain groups of people have more of a right to the resources on Earth. Every human being has an equal right to a fair share of the Earth's resources. However, with a population over 8 billion, even if everyone adopted a modest standard of living the planet would still be pushed to its ecological limits. Unfortunately, the "average person" on Earth consumes resources at a rate over 50% above what is sustainable, and the average American consumes 5 times more than the planet's sustainable yield. As you’re probably piecing together, this is a recipe for an incredibly unsustainable situation. In order to mitigate this situation, we need to first understand the sources of overpopulation, and how this is affecting our Earth, from climate change to socio-political unrest. So let's talk about it.

In biology, we talk about populations in reference to a species carrying capacity, which is the number of individuals of a population that can be sustained by a given area. Once a population exceeds this threshold dieback will inevitably occur due to the ecosystem's limiting factors. These density-dependent factors include disease, competition, and predation, and they can have either a positive or a negative correlation with population size. With a positive relationship, these limiting factors increase with population size, restricting growth. Conversely, with a negative relationship, population growth is limited at low densities and becomes less restricted as it grows. When a species experiences overpopulation, these limiting factors intensify. The species will face higher rates of disease, greater food and water scarcity, and increased predation, all of which lead to a population decline. Humans, however, have altered this dynamic. Thanks to the agricultural revolution and modern medicine, we have effectively mitigated many of these limiting factors. This is great news for all of us on Earth today because we no longer have to worry about these things. However, it has also enabled our population to grow exponentially beyond Earth's carrying capacity.

Besides this, several other factors contribute to this growing population, including declining mortality rates, limited access to contraception, and inadequate education for girls. The primary cause of population growth is the imbalance between births and deaths. Infant mortality rates have decreased significantly, with 4.1 million infant deaths in 2017 compared to 8.8 million in 1990, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Simultaneously, lifespans are increasing worldwide, and current generations are likely to live longer than previous ones, as the global average life expectancy has more than doubled since 1900. These are remarkable achievements, but they contribute to an ever-growing population.

Lack of access to contraception in many parts of the world prevents women from planning their families. In fact, studies suggest that up to 44% of pregnancies worldwide are unplanned. Many studies also show that access to education plays a big role in how many children a woman will have. Although female access to education has increased over the years, the gender gap remains. Roughly 130 million girls worldwide are out of school currently, and an estimated 15 million girls of primary school age will never learn to read and write, compared with 10 million boys. Education among women and girls reduced the amount of children women have by delaying childbearing to later ages, and increased workforce participation.

It’s important to note that women are having fewer children today than ever before. 50 years ago the global Total fertility rate (TFR) was around 5, meaning that on average women in the world had around five children. In 2024, the global TFR is 2.4. Women are on average having less than half of the children than previous generations, yet the global population is still rising – why? That is because there are more women in the age range to bear children than ever before. So even though there are less births on average, the current population increase is estimated at around 73 million people per year.

Overpopulation has many effects on our world, many of which we are witnessing today. As the global population continues to grow, the strain on our natural resources intensifies. More people means a higher demand for food, water, housing, and other essentials. Given the finite nature of these resources, this heightened consumption leads to ecological degradation. Overpopulation is already causing pressures that result in more deforestation, decreased biodiversity, and spikes in pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, all of which exacerbate climate change. Climate change, of course, is making many areas inhospitable due to rising oceans and temperature, is causing the increase in the severity and frequency of natural disasters, and contributing to many other factors that make our world inhospitable for humans.

Socially and economically, overpopulation can strain infrastructure and public services, leading to overcrowded cities, inadequate healthcare, and insufficient educational facilities, which ultimately lead to increased socio-economic disparities. The competition for limited resources can also lead to heightened tensions and conflicts within and between nations, as groups vie for control over water, land, and food supplies. We’re already seeing wars fought over water, land, and energy resources in the Middle East and other regions, and the turmoil is likely to increase as the global population grows even larger.

Moreover, the dense and overcrowded living conditions associated with overpopulation can facilitate the spread of infectious diseases, increasing the risk of pandemics. The ongoing deforestation and habitat destruction also bring humans into closer contact with wildlife, potentially exposing us to new zoonotic diseases.

Overpopulation remains a pressing global issue with far-reaching implications for our environment, resources, and socio-economic stability. Addressing overpopulation requires a multifaceted approach that includes promoting access to education, particularly for girls, and ensuring widespread availability of reproductive health services. Additionally, fostering a collective responsibility to manage Earth's resources sustainably is crucial. This means not only reducing individual consumption levels, especially in more affluent societies, but also supporting policies and practices that encourage sustainable living. While the challenges posed by overpopulation are significant, they are not insurmountable. By understanding the causes and effects of overpopulation and committing to collaborative and equitable solutions, we can work towards a future where both the human population and the planet can thrive. Observing World Population Day serves as a reminder of the urgency of this issue and the need for continued awareness and action to ensure a sustainable and just world for all.

RECENT ARTICLES