FIELD NOTES BLOG

Forest Fungi at Severson Dells

Spring’s right around the corner, which is such an exciting time for nature lovers all around. This is a season filled with new beginnings, growth, fresh blooms, and lots of sprouting. The migrating birds return, ephemeral wildflowers appear, trees begin budding, plants pop up, and fungi begin sprouting!

Believe it or not, fungi are actually everywhere, and they affect our lives everyday! From the mushrooms on your pizza, to life saving medicines, to the mold growing on your leftovers, to the microscopic organisms on pretty much any surface you touch - fungi are everywhere! However, most fungi are just microscopic and require magnification to see with the human eye. This is why mushrooms are so commonly known because they are one of the few species of fungi that are easily seen by the human eye without using any sort of magnification tool.

Mushrooms are mysterious creatures! Not classified as either a plant or an animal, belonging to its own scientific kingdom, but yet essential for survival of all life. Fungi are the backbone of all life that we know on earth. Whether you’re looking to forage and cook them up, or you’re looking just to take a cool picture, mushrooms are always there and ready. You may have heard the terms mushroom and fungi before, and sometimes they are used interchangeably, even though this isn’t correct. The term

mushroom is often used to describe a type of fungi that have gills, a cap, a stem, and it functions as the spore-bearing fruiting-body of a fungus, which grows deeper beneath the surface. Whereas

fungi are organisms that lack chlorophyll and vascular tissue, and that survive by absorbing and decomposing organic matter.

Fungi play a crucial role in nature, by breaking down and recycling nutrients from dead plants and matter into simpler compounds. The simpler compounds then become food for other organisms: this then causes fungi to form symbiotic relationships with other plants and animals in the ecosystem. Unlike plants, fungi do not have roots, stems, leaves, flowers or seeds. Instead, fungi have a mycelium (a root-like structure) which is a network of small, white filaments, and this is what allows them to absorb nutrients and water from the objects they grow in. Fungi are the most similar in structure to plants, yet they still differ significantly, therefore, fungi belong in their own kingdom of organisms.

Severson Dells Nature Center is fortunate enough to have a beautiful display of mushrooms here. Throughout my few months being here at Severson Dells, I have been able to confidently identify at least 12 different fungi species within our forests, each of them thriving with a large population of mushrooms nearby! However, within the last few years there has been a growing concern about the decline of mushroom species found in Illinois, especially within our forests. A large majority of these population declines are due to over harvesting, habitat deregulation, and the expansion of urbanization and agriculture. As a result, fungi species are displaced from an ecosystem they were familiar and thriving with, to a foreign environment that no longer has favorable conditions for them, resulting in their disappearance. To conserve our remaining mushrooms, we must continue to manage our public and private natural areas and forests in ways that protect and maintain mushroom populations.

We always want to caution people that, while it is legal to forage for fungi for personal use on Forest Preserves of Winnebago County preserves, not all fungi are edible and it is best to do your own research on fungi foraging. If you are curious about learning more on mushroom foraging, consider taking a class from a local expert or doing extensive research. The key to safe and sustainable mushroom hunting is education!

Mushrooms Found at Severson Dells

From fertile prairies to rolling hills and lush forests, Illinois offers a diverse landscape for mycology enthusiasts. Having such a variation of habitats makes Illinois an ideal location for

mushroom hunting through all four seasons! Lots of different kinds of wild mushrooms typically begin growing in the spring, around late April to early May. However, not all mushrooms follow this pattern. Different species are more prevalent at different times of the year, but the majority do prefer the spring to fall weather conditions. Here at Severson Dells, we are fortunate enough to have many species of fungi and mushrooms that bloom here, and we appreciate them all! Let’s take a deeper look at the types of mushrooms found here:

Scroll down for more information on each mushroom!

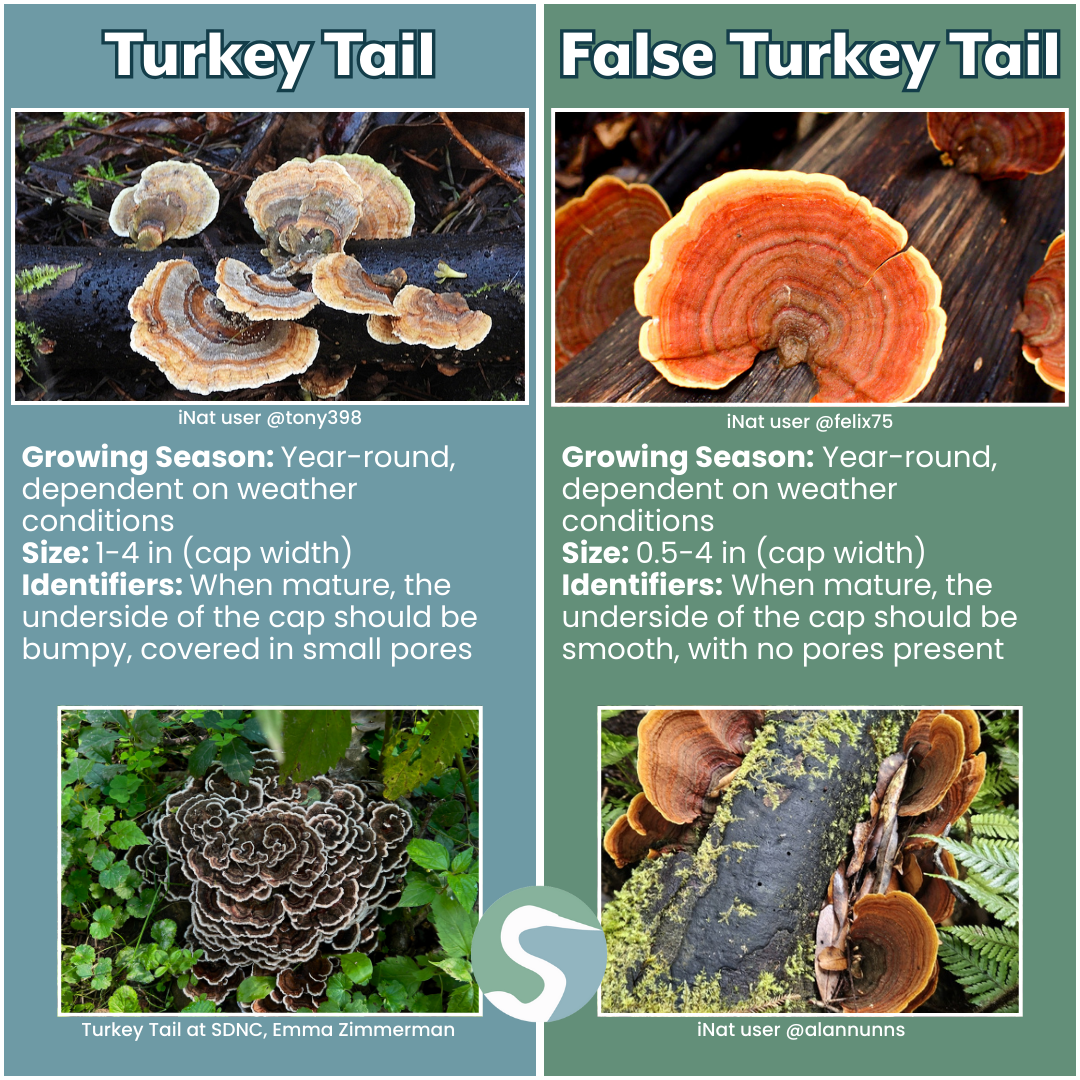

Turkey Tail

Turkey tail mushrooms are exactly what they sound like - mushrooms that have an appearance similar to a turkeys’ tail! Year-round, turkey tail mushrooms can be found, however, they are most commonly seen at the end of August or early September, through the fall, and into the winter months. These mushrooms are often found sprouting along stumps and logs of deciduous trees, and they always grow in groups, clusters, or rows, and will be layered. A mature turkey tail will have a fan-like appearance, with individual semi-circle shapes, called caps (~1-4 inches across), that have concentric bands of color following the semi-circle shape. Each cap is typically a few millimeters thick, has a band of white along its ruffled edge, has concentric bands usually in shades of brown, red, gray, yellow, or orange, and will have a leathery texture. When identifying this mushroom, flipping it over and viewing the underside of a cap is essential, as the false turkey tail appears similar but has a differing underside appearance. The underside of a turkey tail mushroom should be white and covered in small pores, which you should be able to see and feel when running your finger across it.

False Turkey Tail

Similar to the turkey tail mushroom, the false turkey tail mushroom looks almost identical, yet it’s a completely different species of mushroom! False turkey tail mushrooms will grow year round, however, they are most commonly seen at the end of August or early September, through the fall, and into the winter months. These mushrooms are commonly found sprouting along decaying logs and stumps and they always grow in groups, clusters, or rows, and will be layered. A mature false turkey tail will have a fan-like appearance, with individual semi-circle caps ~0.5-4 inches across, that have concentric bands of color following the semi-circle shape. Each cap is typically a few millimeters thick, has a band of white along its ruffled edge, has concentric bands usually in shades of brown, red, gray, yellow, or orange, and will have a hairy, leathery texture. The underside of a false turkey tail mushroom should be a variant of gray or yellow and slightly leathery but also smooth, with no pores present. If pores are present then you have found its lookalike mushroom, the turkey tail!

Giant Puffball

Typically beginning in July or August, and continuing into October and November, giant puffball mushrooms will sprout near forest openings, in meadows, or underneath trees on pieces of rotten wood. Giant puffballs are very commonly found throughout Illinois, and as of August 2024, they are the official state mushroom of Illinois! A mature giant puffball can range in size from a softball to up to 2 feet across, it will be round (as the name suggests) or potato shaped, and will have a white to gray cap which will turn greenish yellow with age, and then gradually to a dark tan as the spores mature. These mushrooms are soft and spongy, with a smooth texture that turns slightly bumpy as the spores mature.

Orange Mycena

From June to September,

orange mycena mushrooms will sprout in dense clusters on deciduous trees. These mushrooms often grow in thick, dense, overlapping clustered formations, with multiple stems emerging from a single point. A mature orange mycena will typically have a yellowish-orange stem that’s 3-7 inches, is curved with a smooth texture that becomes sticky when wet, and the base is covered in dense, coarse hairs. The cap is similar in color to the stem, is 0.5-2 inches in width, is rounded but becomes flattened towards the edges, and sometimes they will have a slight depression in the center that appears darker. The cap is smooth and sticky when wet, but the underneath of the cap will have gills that are a bright reddish-orange color, with a pale orange color between them.

Morel

Morels are some of the most sought after edible mushrooms in the world, due to their unique flavor and the fact that they grow wild, so it’s special to find them! Once a year, for three to six weeks in May and lasts through early June, morel mushrooms will quickly appear, flourish, and then disappear in forested areas, typically near streams and creeks. Morels are known to appear on and near dying trees, among fallen pine needles, as well as at burn sites. A mature morel will typically stand between 3-4 inches tall, will have a white or cream stalk, and will have a distinct blonde or gray pitted honeycomb cap, with a sponge-like texture.

Dryad’s Saddle (pheasant back)

From April to August,

Dryad’s saddle mushrooms (also known as pheasant back mushrooms) will sprout in dead wood from the heart rot (a fungal disease that causes the decay of a tree’s central wood of the trunk and branches) of living trees, as well as on dead wood. Therefore, dryad’s saddle is a wood-decay fungus that grows as a parasite. A mature dryad’s saddle can grow 3-12 inches in width, in a singular or multiple layered caps making a fan-shaped appearance, will be brownish color and is typically covered in large dark-brown to black scales (their pattern and coloration are similar looking to a pheasants feathers, hence the name), has an off-centered cream colored stalk, and tend to reappear in the same locations often fruiting more than once a year.

Golden Oyster

Throughout the Spring, Summer, and Fall, golden oyster mushrooms will sprout along damaged stumps, logs, and rotten wood. Golden Oyster mushrooms have a short shelf-life once they start fruiting in the wild, typically lasting only a few days to a week before eventually deteriorating, but this is dependent on the moisture levels (wetter conditions will slow down the rate of deterioration). A mature golden oyster mushroom will typically be growing in a small to medium sized clump (these are referred to as bouquets because of the resemblance), will consist of many layers of tightly packed mushrooms with bright yellow caps ranging from 2-6 centimeters in diameter, and they will be held up by curved, white stumps that are typically 2-5 centimeters in length. Golden oyster mushrooms are known to be very fragile and easily break apart, and to have a spongy texture and a fresh scent that people often say reminds them of watermelon.

Native Oyster

Typically,

native oyster mushrooms will begin sprouting in April or May and you can find them up until October or November. They will sprout along damaged stumps, logs, and rotten wood. Native oysters have a short shelf-life once they start fruiting in the wild, typically lasting only a few days to a week before eventually deteriorating, but this is dependent on the moisture levels (wetter conditions will slow down the deterioration). A mature native oyster will typically be growing as a cluster with many other native oysters, or they may be growing singularly, will have fan-shaped, white, gray, or light yellow caps that are ~10 inches wide, and if a stem is present, it will be less than 0.5 inches in length and curved.

Wood Ear

From May to November, wood ear mushrooms will sprout on fallen logs or decomposing branches, and they will typically grow in clusters with lots of other wood ear mushrooms. A mature wood ear can grow 1-6 inches in width, less than 3 inches tall, are cup-shaped or ear-like (hence the name), and have a wavy cup. They are brown to dark brown in color, covered in tiny hairs that make the caps feel fuzzy, are gelatinous when young but will harden and turn brittle as the fungi ages; so because of this you will typically be able to find wood ear’s during cooler, wet conditions, such as after it’s been raining.

Mica Cap

Mica cap mushrooms are often some of the first mushrooms to appear in the spring, typically sprouting up a few days after heavy rainfall, along fallen logs, branches, dying trees, and buried wood. A mature mica cap can grow 2-5 centimeters, will be bell-shaped, light brown, amber, or cream in color, and will turn a more muted color as they age. They will have a white stem 2-8 centimeters long and it will be smooth to the touch as the stem is covered in very fine hairs. Typically, mica caps like to grow in clusters, so you will almost never find these on their own! Their caps are covered in a layer of white, glistening speckles that resemble the mineral mica (hence the name), however, these speckles don’t last for very long, and they’re commonly washed away after the first rainfall that they’re exposed to.

Honey

From August to November, honey mushrooms will sprout in clusters at the bases of trees and stumps, typically after heavy rainfall. Honey mushrooms parasitize trees, so once it’s appeared there’s no getting rid of it, even if you cut the tree down; the mushrooms will still sprout seasonally from the stump. A mature honey mushroom cap can grow 1-6 inches wide, with a whitish stalk that’s ~2-6 inches long, and has an identifying white ring located underneath the cap, at the top of the stalk. They will have a convex cap, that’s yellow or brown in color and has a sticky texture with blacky, hairy scales in the center.

Little Nest Polypore

Upon first glance, this mushroom may easily be confused with some other lookalikes, such as turkey tail or birds nest polypores, however, there are a few ways to tell if the fungi you’re looking at is a little nest polypore. The easiest way to tell if you’ve found a little nest polypore is to find them while they’re still young, because when young they have very folded over cup-like appearances. From June to December, little nest polypore will sprout individually along the branches of dead and dying trees, and as they age they will slowly decompose, leaving behind a small, circular, nest-shape (hence the name) except without any eggs inside. A mature little nest polypore can grow 1-5 centimeters, will be concentrically zoned with white, brown, or gray, and at the base they will have a whitish stalk that holds the cups above the tree, giving these fungi a difficult appearance to identify.

Severson Dells Nature Center is lucky enough to have the 12 mushroom species just discussed growing here in our forests! There’s likely more species here, this is just all I’ve seen in the last few months, and I’m new to foraging. So, be sure to stop by Severson Dells, take a stroll around, and let us know how many mushroom species you were able to identify!

Sources:

“Stages of Mushroom Growth (& What Growers and Consumers Should Know).” Become Lucid, becomelucid.com/blogs/news/stages-of-mushroom-growth-amp-what-growers-and-consumers-should-know.

Walker, D.H., and M.R. McGinnis. “Pathobiology of Human Diease.” ScienceDirect Topics, www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/fungi#:~:text=Fungi%20are%20eukaryotic%20organisms%20that,relationships%20with%20plants%20and%20animals.

“Wild about Illinois Fungi!” Illinois Department of Natural Resources, dnr.illinois.gov/education/wildaboutpages/wildaboutfungi.html. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

McFarland, Joe. “Fungus Fans.” Outdoor illinois October 2007 Fungus Fans (Turkey Tail. dnr.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/dnr/oi/documents/oct07turkeytailmushrooms.pdf.

“False Turkey Tail.” Missouri Department of Conservation, mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/false-turkey-tail.

“Giant Puffballs: Herbarium.” Utah State University, www.usu.edu/herbarium/education/fun-facts-about-fungi/giant-puffballs#:~:text=Giant%20puffballs%20are%20found%20in,ground%20or%20on%20rotten%20wood.

“False Turkey Tail.” Missouri Department of Conservation, mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/false-turkey-tail.

Hagerty, Jim. “It’s Morel Season. There Is Still Plenty of Hunting Left in the Rockford Area.” Rockford Register Star, Rockford Register Star, www.rrstar.com/story/news/2022/05/20/tips-hunting-morel-mushrooms-rockford-illinois/9811394002/.

Schmit, John Paul. “Springing up - Dryad’s Saddle (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/articles/000/dryads-saddle.htm.

“Golden Oyster Mushrooms.” Specialty Produce, specialtyproduce.com/produce/Golden_Oyster_Mushrooms_7033.php#:~:text=Golden%20oyster%20mushrooms%20grow%20in,in%20appearance%2C%20depending%20on%20age.

“Oyster Mushroom.” Illinois.Gov, Illinois Department of Natural Resources, dnr.illinois.gov/education/wildaboutpages/wildaboutfungi/m-z/wafnoystermushroom.html#:~:text=The%20oyster%20mushroom%20may%20be,appear%20singly%20or%20in%20clusters.

Floris. “Wood Ear Mushroom Growing Guide.” Mushroology, Mushroom Growing and Cultivation, mushroology.com/wood-ear-mushroom-growing-guide/.

Kuo, Michael. “Coprinellus Micaceus.” MushroomExpert, www.mushroomexpert.com/coprinellus_micaceus.html.

“Honey Mushroom.” Missouri Department of Conservation, mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/honey-mushroom.

Emberger, Gary. Poronidulus Conchifer, www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/poroid%20fungi/species%20pages/Poronidulus%20conchifer.htm#:~:text=Common%20names%3A%20Little%20nest%20polypore.&text=decaying%20deciduous%20wood%3B%20June%20through,caps%201%2D5%20cm%20wide.

RECENT ARTICLES