FIELD NOTES BLOG

How a Walk in the Woods Can Change the World

The Profound Power of Aesthetic and Sensory Delight in Natural Spaces to Change Our Relationship to the Environment

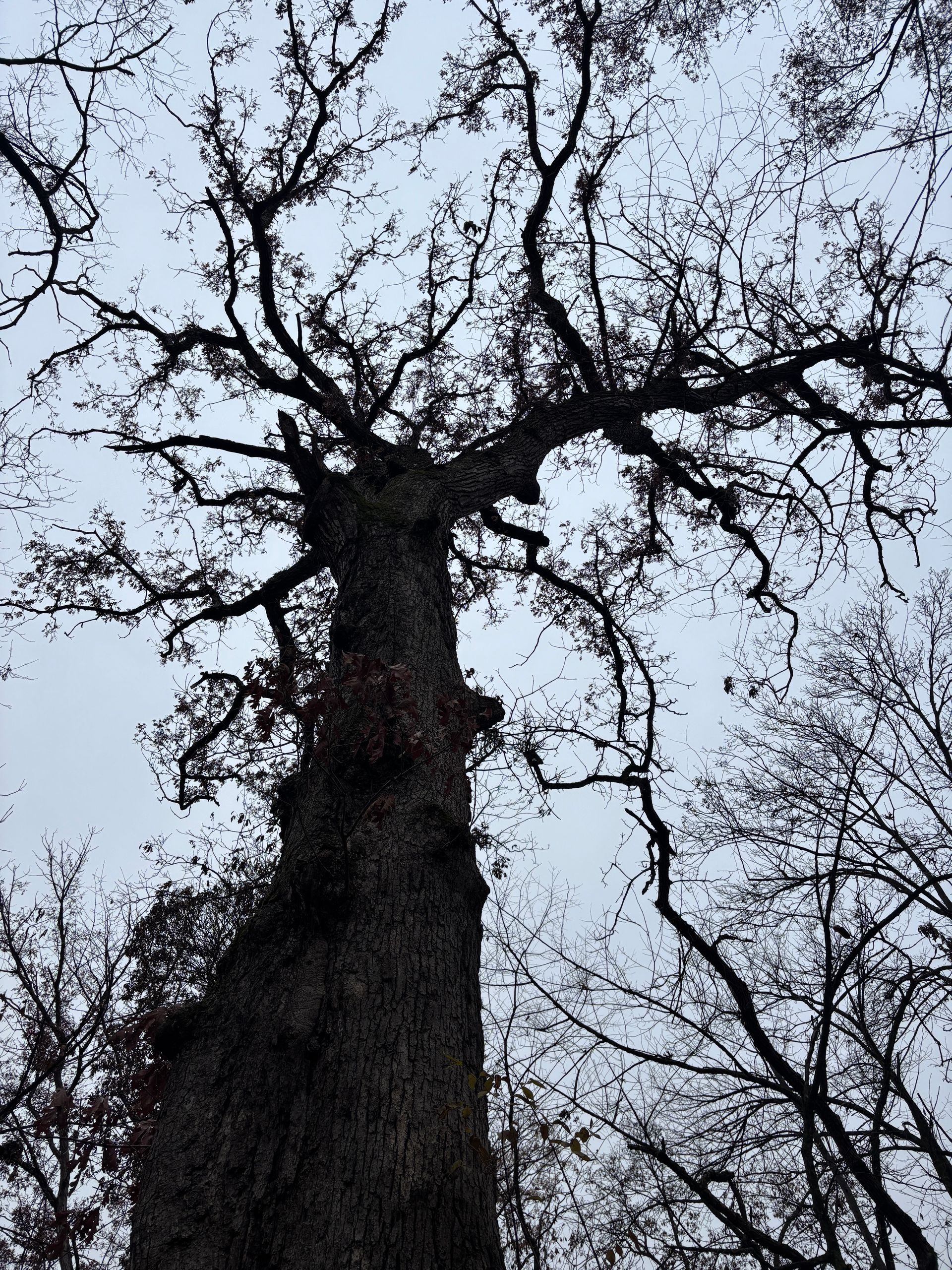

On the week of the first snow of the season I walked into the woods during the middle of the day, the sun high and the trees bowing, snow bright over the undergrowth and white up the trunks, the faint musty smell that hangs above the grounded late fall leaf decay still lingering.

I craned my neck upward to see the branches dance, responding to the strengthening sound of those brown leaves which still remained hanging moving against each other, spurred on by the wind, the same wind I felt sharp and cold and strange against my fingers. I had been held in quiet attention to the sound since I walked out the door of the nature center, practicing without effort what is sometimes known as involuntary attention, which is thought to be engaged by time spent immersed in natural spaces (Kaplan; Schertz, Bergman). There is support, in fact, for contact with nature such as this generally strengthening attentive capacity, and improving cognitive ability in a variety of ways, such as memory recall (Schertz, Bergman; Bratman et al.).

As I continued my walk, looking up at these nearly wintering trees, I curiously followed the spindly paths of their bare branches, which progressed into small and smaller brown iterations(versions) of their central, sturdy trunks. These progressions of patterned forms into smaller and smaller scales, also known as fractals, are abundant in dense natural ecosystems, and have been shown to soothe stress in humans when we gaze at them (“Fractals in Nature”; “Fractals in psychology and art”;

Taylor et al.).

Recent theories suggest that they create such aesthetic enjoyment due to their compatibility with the patterns of human visual processing in the brain, saying essentially that our bodies may have evolved to feel comfortable and relaxed by having fractals in our environment. There is now even research suggesting that these effects may go beyond the visual, and that naturally occurring fractal forms are present in some of the sounds we can hear or objects we can touch in our natural ecosystems as well, providing a myriad of calming sensory effects (“Fractals in psychology and art”; Taylor et al.).

As my gaze fell back down eastward, it caught for a moment straight out, at the places between the fuzzy textures of the tree tops and forest floor, enjoying the windows created between trunks. Being in a place with trees positioned just so, with their bark-split brown bodies placed an average of 3 meters away from each other (called medium-density) has been shown to relax humans both physically and psychologically(Ramanpong et al.).

I continued moving beneath their canopy down the path, looking down at my cold hands, flexing them, seeing through my chilly skin the fractal shape of my own blood vessels, becoming an object of my own natural observations. I recalled a child asking me some weeks ago on a hike, at about this same place on the path, if humans are a part of nature. Yes, was my answer, one often forgotten where it sits embedded at the roots of humanity’s modern relationship to the planet.

Anecdotally, I know many children and adults–myself included–have this question tumbling through our heads, as we all try to make sense of our physical realities (from rural to urban to everywhere in between) in places heavily altered by human activity, both active and passive

Just then I felt the sun hit my face through the branches, its bright rays touching my skin in warm patches, bringing a smile to my cheeks. I love the way the sun feels in any season. I reached down then where I stood and picked up a twig, its rich dark wood covered in circled patches of yellow and turquoise lichen, woven with vibrant green moss, moss which was soft under my fingers.

Staring into this small, tubed pile of life in my hands brought me such enjoyment, the chorusing colors satisfying something nameless in me. Such aesthetic and sensory joy I felt from these colors and textures seems akin to the one scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes of as being her impetus to study biology–her youthful staring at wildflowers kindling in her the question: why do the astor and goldenrod look so good together? (Kimmerer)

All of these sensory delights also brought to mind a discussion I’d had with students visiting the

nature center on a recent field trip, while they were building forts made of tree branches. One group commented that their fort was better than the other because it was designed to ensure primarily the security and safety of its inhabitants, in comparison to the goal of the other group, who explained the reasoning behind their construction choices as “because it looked nice”.

I chatted with the students about this comment, suggesting that maybe a difference in values, one of safety, and the other aesthetics, rather than poor design choices, were really what lie behind their differing fort designs.

Later, though, I reflected on how I knew, with such conviction to explain to kids, that aesthetics were a value just as deserving of that label as something so easily recognizable as important to effective human manipulation of our environment as safety. This reflection brought up a more fundamental one–why is aesthetic and sensory enjoyment worth indulging at all in regard to our natural places, especially when, in our time there are such visible scars of human whim cut into

more-than-human living systems across the globe.

There are, as we explored earlier, obvious benefits to human immersion in natural ecosystems found in its profound positive impacts on our physical and psychological health. Why, though, does this time in nature, and within it our indulgence of seemingly frivolous aesthetic and sensory joys (such as staring gleefully at bright orange lichen, stopping to touch cool creek water, reflecting for a moment longer on how good the sun feels on skin, listening to faint bird song, running a hand over the messy forest floor) matter on more than the scale of an individual, self-focused pursuit of health? How could pursuing enjoyment in natural systems ever be beneficial to anyone or anything other than ourselves?

For one, it is, as Kimmerer imparts in her own indulgence of visual aesthetic delight looking at flower coloring, a new way of asking questions that can further collective ecological understanding.

Following our aesthetic and sensory enjoyment in nature can take us to other places, too. To better contextualize where we’re headed, let’s first take a moment to look at what joy really is. What does it mean for one to enjoy or take delight in something? According to the American Psychological Association, joy is “a feeling of extreme gladness, delight, or exultation of the spirit arising from a sense of well-being or satisfaction,” and enjoyment is “a perception of great pleasure and happiness brought on by success in or simple satisfaction with an activity”(“Joy”, “Enjoyment”).

What joy is and why it’s valuable is also something meditated on by many contemporary social thinkers, such as author and gardener Ross Gay. Reflecting on his writings in

The Book of Delights, where he wrote a short essay on something which brought him joy each day for a year, he shared, “...to me, joy has nothing to do with ease. And joy has everything to do with the fact that we’re all going to die. That’s actually — when I’m thinking about joy, I’m thinking about that at the same time as something wonderful is happening, some connection is being made in my life, we are also in the process of dying. That is every moment. That is every moment”(“On the Insistence of Joy”). Gay believes joy is not out of reach during times of struggle, and may even be integral to our experience of it.

Joy is not taken in delusion to reality, but entangled within it–a particularly notable definition when considered in regard to our modern experience of natural systems, about which we are likely also experiencing a level of grief.

Another author, Adrienne Maree Brown, also thinks much about the profound societal shaping power of enjoyment: ““Laughter is important. Joy is important. It’s not a guilty pleasure, it is a strategic move towards the future we all need to create. One in which our children are laughing, our children are free. They can go wherever they need to go. There are no borders holding them. That is what I am living and loving for”(“Holding on to Joy”). The idea that Brown presents here, that taking joy can be a first step toward positive change, is connected to Gay’s: things don’t have to be going perfectly in the world for us to experience enjoyment within it, and in fact the joy itself can inform us–by teaching us what good, joyful existence feels like, looks like, acts like–about how to move through challenging times.

It does this by providing a direction toward an envisioned future, a vision learned through feeling sensory and aesthetic delight (for example, a part of the envisioned future I have imagined through my own joyful experiences is one where a child could leave for school in the morning and see the soothing shapes of dense, mature trees, and the sound of cars is quiet enough that they can hear the leaves in the canopy sway). The more we know what joy feels like, the more it becomes a part of how we understand our realities and imagine what’s possible.

These ideas are coming not only from philosophy and sociology–there is also emerging scientific research that supports the idea that sensory experience and enjoyment in nature is connected to our relationship to the environment, and subsequently our positive behaviors to care for it.

In one study, researchers in the Abancay area of Apurimac, Peru, demonstrated how sensory, and emotional experience (aesthetic perception included) are a part of people’s formation and description of their relationship to the natural world(Pramova et al.). Other studies have found positive correlations between time spent in and exposure to nature and proenvironmental behaviors generally(Alcock et al.; Whitburn et al.). Lastly, researchers in Badaling National Forest Park in China, found that people’s proenvironmental behaviors were positively correlated specifically to their sensory experience in natural ecosystems(sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch). Experiences of nature, positive emotions, and feelings of attachment to the place all were a part of this sensory experience transforming into proenvironmental behavior(Yu, Zhou, and Tan).

This body of thought and research points back to the idea that sensory and aesthetic experiences in nature are valuable, not just as a means for one individual to experience enjoyment or good health, but also as a critical foundation for proenvironmental behavior, the kind of behavior that has profound positive implications for all living systems.

To find what we enjoy in nature, to explore the natural world through our senses, can actually be the starting point for positive, collective restructuring of our relationship to the environment broadly. It can maybe feel frivolous or even harmful to get in touch with our sense of delight as a way to engage with natural places, or perhaps it feels like there is no point in being immersed in and getting to know a world already so affected by large-scale ecological changes. Learning how to care for and respect natural systems, though, is something that can only happen if we get to know them.

If we know them, we regain our understanding of how to be mindful of them. As humans, it is not our enjoyment of nature we have to fear for our long-term planetary health, but rather our forgetting that it is our birthright as living beings on this planet to take delight in and enjoy enmeshed relationships with all other life.

Bibliography

- https://backend.production.deepblue-documents.lib.umich.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/5feb1395-53cb-4712-b82e-feaf75e81be0/content

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0963721419854100

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aax0903

- https://www.mindfulecotourism.com/fractals-in-nature/

- https://blogs.uoregon.edu/richardtaylor/2016/02/03/human-physiological-responses-to-fractals-in-nature-and-art/

- https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/e/12535/files/2024/04/978-3-031-47606-8_45-930c4fed1c89f1c2.pdf

- https://dictionary.apa.org/joy

- https://dictionary.apa.org/enjoyment

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266671932400058X

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S161713812500281X#b0215

- https://www.kqed.org/podcasts/521/holding-on-to-joy

- https://onbeing.org/programs/ross-gay-on-the-insistence-of-joy/

- Gay, R. (2022). The book of delights. First paperback edition. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

- https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pan3.10286

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019313492?via%3Dihub

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0013916517751009

Background Knowledge

- https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/04/nurtured-nature

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-44097-3

- https://atmos.earth/ecological-wisdom/embracing-the-more-than-human-through-law-and-language/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494424002524?via%3Dihub

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0013916508319745

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

- https://dictionary.apa.org/eudaimonic-well-being

- https://dictionary.apa.org/hedonic-well-being

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/48591543?read-now=1&seq=9#page_scan_tab_contents

- https://earth.org/human-connection-with-nature/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8305895/

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

- https://efi.int/publications/what-types-nature-exposure-are-associated-hedonic-eudaimonic-and-evaluative-wellbeing

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8125471/#B1-ijerph-18-04790

RECENT ARTICLES