FIELD NOTES BLOG

Winter Wetlands

What is a wetland?

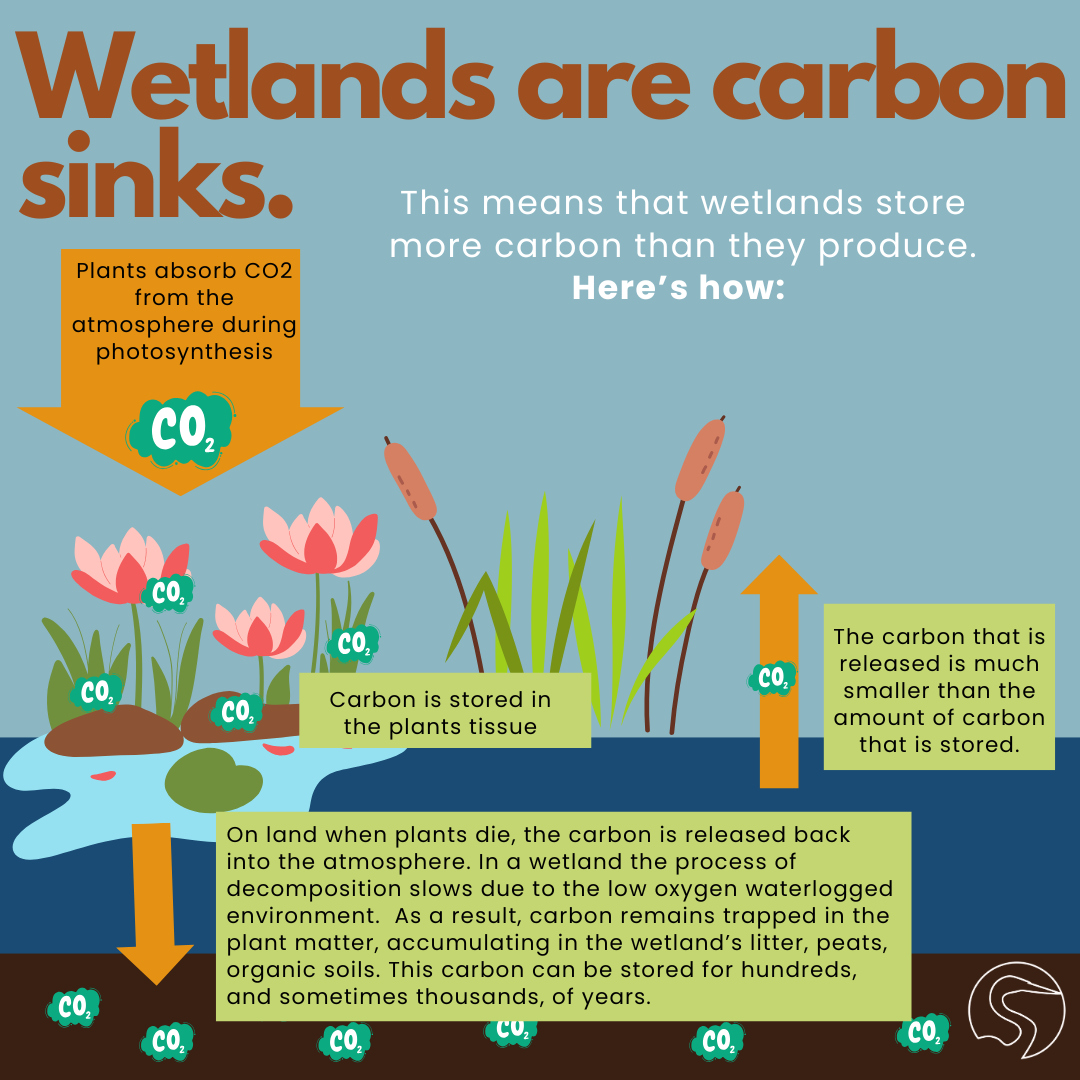

You may be familiar with wetlands (think bogs, marshes, swamps, and peatlands), but did you know these ecosystems play a crucial role in mitigating climate change? Wetlands are highly effective carbon sinks, meaning they capture and store carbon that would otherwise contribute to global warming. This function is particularly important in the winter months when many ecosystems slow down, yet wetlands continue to trap and store carbon, even under layers of ice and snow.

To understand how wetlands act as carbon sinks, it’s helpful to first revisit the concept of carbon. Carbon is a chemical element found in various forms, one of the most notorious being carbon dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas that traps heat in the Earth’s atmosphere. Since the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels have risen dramatically, contributing to global climate change.

Plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and use it to build new tissue, storing it in their roots, stems, and leaves. When plants die on land, they decompose, releasing the stored carbon back into the atmosphere. However, the process of decomposition is much slower in wetlands. The waterlogged conditions limit the amount of oxygen available to decomposers, preventing the full breakdown of dead plant material. As a result, carbon remains trapped in the plant matter, accumulating in the wetland’s litter, peats, organic soils, and sediments that have built up. Wetlands can effectively store this carbon for hundreds, and in some instances, thousands, of years. This long-term storage helps reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, making wetlands an essential natural solution to climate change.

How Does Winter Affect Wetlands?

Although wetlands may appear dull and lifeless on the surface during winter, significant processes are still occurring beneath the ice and snow. Cold temperatures slow the rate of decomposition, allowing organic matter to accumulate in the soil and enhancing its ability to store carbon. This effect is particularly pronounced in northern permafrost peatlands.

Peatlands, which are a type of wetland, store twice as much carbon as all of the world’s forests combined! Permafrost peatlands, which are found in Arctic and subarctic regions of countries like Canada, Russia, and the United States, contain a thick layer of peat, which is decomposed plant material that has accumulated over millennia. The freezing temperatures in these regions prevent the peat from fully decaying, allowing it to build up over thousands of years. In these wetlands, cold temperatures are essential to preserving stored carbon.

However, the Arctic is warming at twice the rate of other regions, causing permafrost to thaw. As the permafrost melts, microbes begin breaking down the organic material in the peat, releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. This release of gases accelerates climate change, creating a feedback loop: rising temperatures cause more permafrost to thaw, which releases more greenhouse gases, which in turn leads to further warming, causing more permafrost to thaw, and so forth. This cycle amplifies the impact of climate change, posing a significant threat to global carbon storage and climate stability

What Happened To Midwest Wetlands?

Permafrost peatlands are not the only wetland that is in trouble. For a long time, wetlands were regarded as wastelands unfit for building or farming, and in need of our intervention to make them useful. This mindset contributed to the significant loss of wetlands in the Midwest. In Illinois, wetlands were once a defining feature of the landscape, but over the past few centuries, more than 90% have disappeared due to draining and tiling. Early settlers created drainage ditches and installed underground pipes, or tiles, to quickly channel water off the land and into local streams and rivers. According to the 2017 US Census of Agriculture, approximately 39% of Illinois cropland is covered by tile drainage. As a result, much of Illinois’ landscape, once dotted with water-retaining depressions, became dry and ready for farming and development. Now, less than 5% of the Midwest’s original wetlands remain, and the state’s hydrology has been drastically altered. This is especially problematic, as wetland are vital for recharging aquifers by collecting surface water from rain and runoff, then slowly allowing it to percolate through the soil and into the underlying groundwater. In areas with tile drainage, this process can no longer occur.

The Vital Role Wetlands Still Play

Today, we have a much deeper understanding of the critical functions wetlands perform. Acting as natural filters, wetlands remove sediment and impurities from water. Like a sponge, they absorb water from heavy rains or snowmelt, helping to prevent flooding. Like a nursery, wetlands provide rich, safe habitats for numerous species to raise their young. And of course, like a sink, they store carbon. According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, terrestrial wetlands in the continental U.S. store a total of 13.5 billion metric tons of CO2. Peatlands in the forested regions of the East and Upper Midwest hold the most carbon, accounting for nearly half of all wetland carbon storage in the United States.

Wetlands, though often overlooked and misunderstood, play an indispensable role in our environment, especially during the winter months. These ecosystems not only provide essential services such as carbon storage, water filtration, and flood prevention, but they also support biodiversity by offering safe habitats for countless species. The warming of the Arctic and the ongoing loss of wetlands across the Midwest highlight the urgent need for action to protect and restore these vital habitats. As we face the challenges of climate change, understanding and preserving wetlands is more important than ever. By safeguarding these natural carbon sinks, we can help mitigate global warming and ensure the health and resilience of our planet for future generations.

Sources:

Carbon Sequestration in Wetlands- Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources

Peatlands store twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests- United Nations Environment Program (UNEP)

Wetlands Habitat Management - Illinois Department of Natural Resources

‘We should have a sense of urgency’ as farm drainage tile drives nutrient pollution- Investigate Midwest