FIELD NOTES BLOG

Shifting Signs of Spring

Despite winter being in full swing, many of us are counting down the days until spring We are daydreaming about the tell-tale signs that winter is fading: skunk cabbage flowers poking up through the melting snow, swollen creeks rushing past, the earthy aroma of geosmin in the air, and the high pitch calls of chorus frogs and spring peepers. However, as we think about spring we may also notice how the transition to spring seems to be getting more erratic and happening earlier in the year. For example, as I write this in January it is 11°F outside, but in just a couple of days, the high temperature is forecasted to be 42°F. This strange weather is not just happenstance, it is a sign of our climate changing. Here in Northern Illinois, the average spring temperature has increased by 1°C (1.8°F) in the past 50 years, and it will continue to increase in the future if current global greenhouse gas emission rates continue. This increase may not seem like a big deal, but even a tiny temperature change can cause major ecosystem disruption.

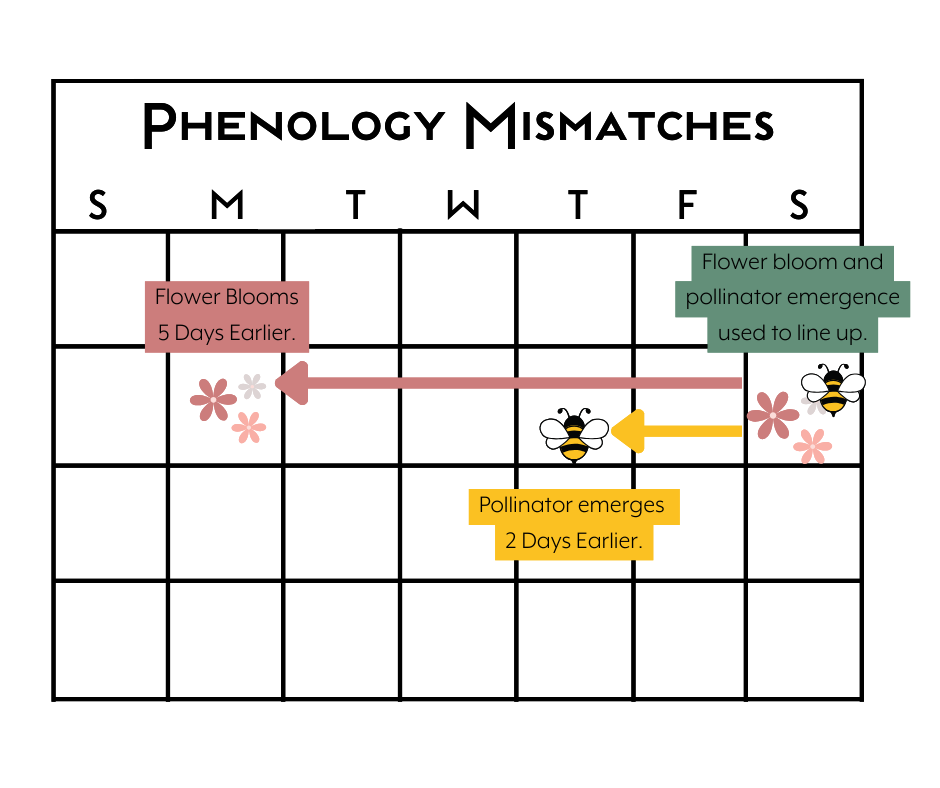

While a bit of an earlier spring may seem nice to those of us who tire of winter in December, it negatively affects our ecosystems by disrupting the timing of key events in the cycles of living things. The study of these cycles is called phenology, and it involves all of the recurring events in an organism’s life cycle such as migration, hibernation, breeding, blooming, and more. Disrupting these rhythms can damage ecosystems because organisms have evolved to rely on each other for reproduction and metabolism at certain times in their cycles in a process called coevolution. Problems arise because organisms rely on different factors when timing their cycles, for example, a flower might bloom based on day length, but the pollinator for that flower might rely on temperature for its spring emergence. The web of connections between organisms is incredibly complex, making it difficult to predict all of the changes that climate change will bring to our ecosystems. However, spring warming has been shown to affect bird migration, plant flowering and leaf out, insect emergence, amphibian arousal from hibernation, and many other key events in plant and animal cycles.

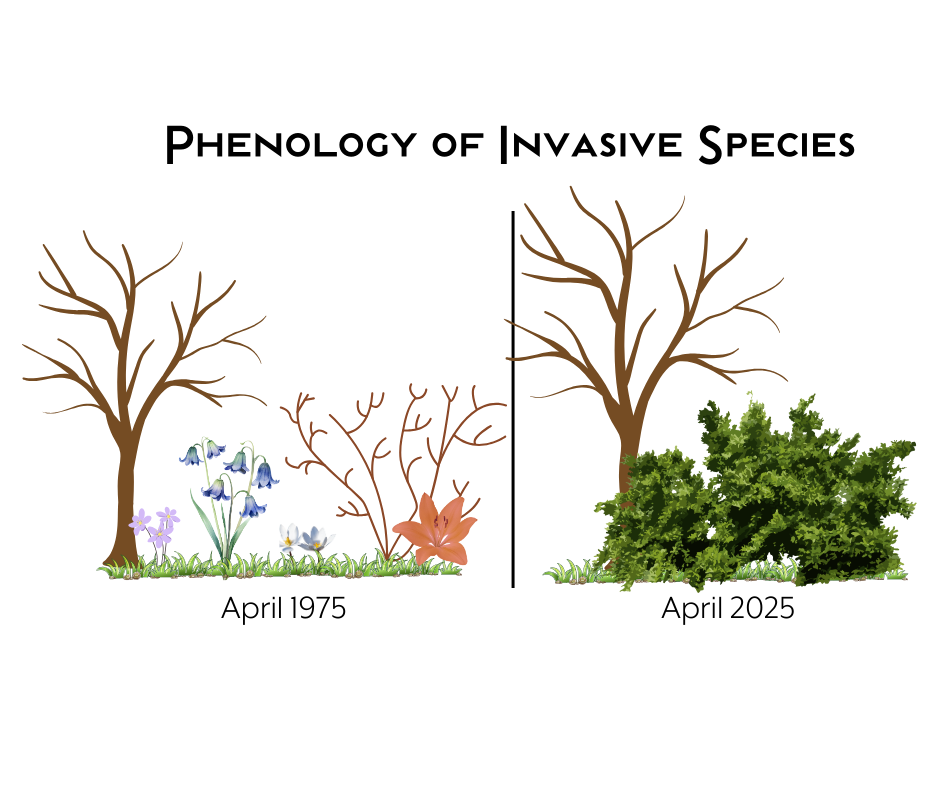

The impact of climate change on the phenology of plants and animals is one of the many ways that the climate and biodiversity crises are connected. The global reduction in biodiversity has made ecosystems more vulnerable to phenological mismatches as organisms may already have fewer food sources, pollinators, or carriers, and are thus more susceptible to changes in timing. Locally, the biggest impact of climate change on biodiversity through phenological change may be the proliferation of woody species in our prairies, woodlands, and savannas. The leaf out and flowering of woody plants is more responsive to warming than herbaceous plants, and thus they are increasingly able to outcompete herbaceous plants for valuable sunlight earlier in the year. This ultimately lowers the biodiversity of our native ecosystems, showing why ecosystem restoration will continue to be important as we mitigate and cope with the effects of climate change.

Studying changes in phenology can be challenging because it requires large data sets that have consistent sampling over long periods of time. Creating these kinds of data sets is tricky because people in the past did not often have the same standards for random sampling that we do today. Community science projects like Bud Burst help to alleviate this problem by training volunteers to collect data on when key events like blooming occur. This way researchers can have data sets that are so large that they remove some of the issues with biased sampling, as long as volunteers are well trained and have easy to follow protocols.

Changes in phenology due to climate change highlight the need to conserve and restore land with the changing climate in mind. Dr. Kimberly Hall, climate change ecologist with the Nature Conservancy, suggests that we do this by creating connectivity between conserved lands, making lands that are managed for commercial purposes more suitable for wildlife, removing invasive species, changing our priority from protecting individual species to protecting landscapes that promote biodiversity, and utilizing green infrastructure that increases biodiversity rather than lowering it. While we may lose species to climate-related extinction, we have the power to prevent more extinctions by conserving and reconstructing dynamic and resilient ecosystems.

Sources

https://www.climatecentral.org/climate-matters/2024-spring-package

https://www.usgs.gov/news/when-timing-everything-migratory-bird-phenology-changing-climate

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10124540/#:~:text=Prior%20studies%20on%20long%2Dterm,per%201%20%C2%B0C%20in

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214574522000323#:~:text=Insects%20shift%20phenology%20in%20response,with%20seasonal%20timing%20%5B11%5D.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9879156/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10124540/#:~:text=Prior%20studies%20on%20long%2Dterm,per%201%20%C2%B0C%20in

https://budburst.org/

https://glisa.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MTIT_Biodiversity.pdf

RECENT ARTICLES