Hundreds of thousands of feet above us there is a mysterious world of elves, sprites, pixes, trolls, and gnomes. I’m not talking about middle earth, but about the rare phenomenon of transient luminous events (TLEs). TLEs are electrical discharges similar to lightning that occur in the upper atmosphere miles above thunderstorms. These mystifying electrical events are so beautiful and elusive that scientists couldn’t help but give them equally mythical names. In this blog we’ll explore the science of these nearly magical events, the questions that are still baffling scientists, how you can photograph them to contribute to community science, and what we can do to reduce light pollution to keep our skies magical.

Lightning

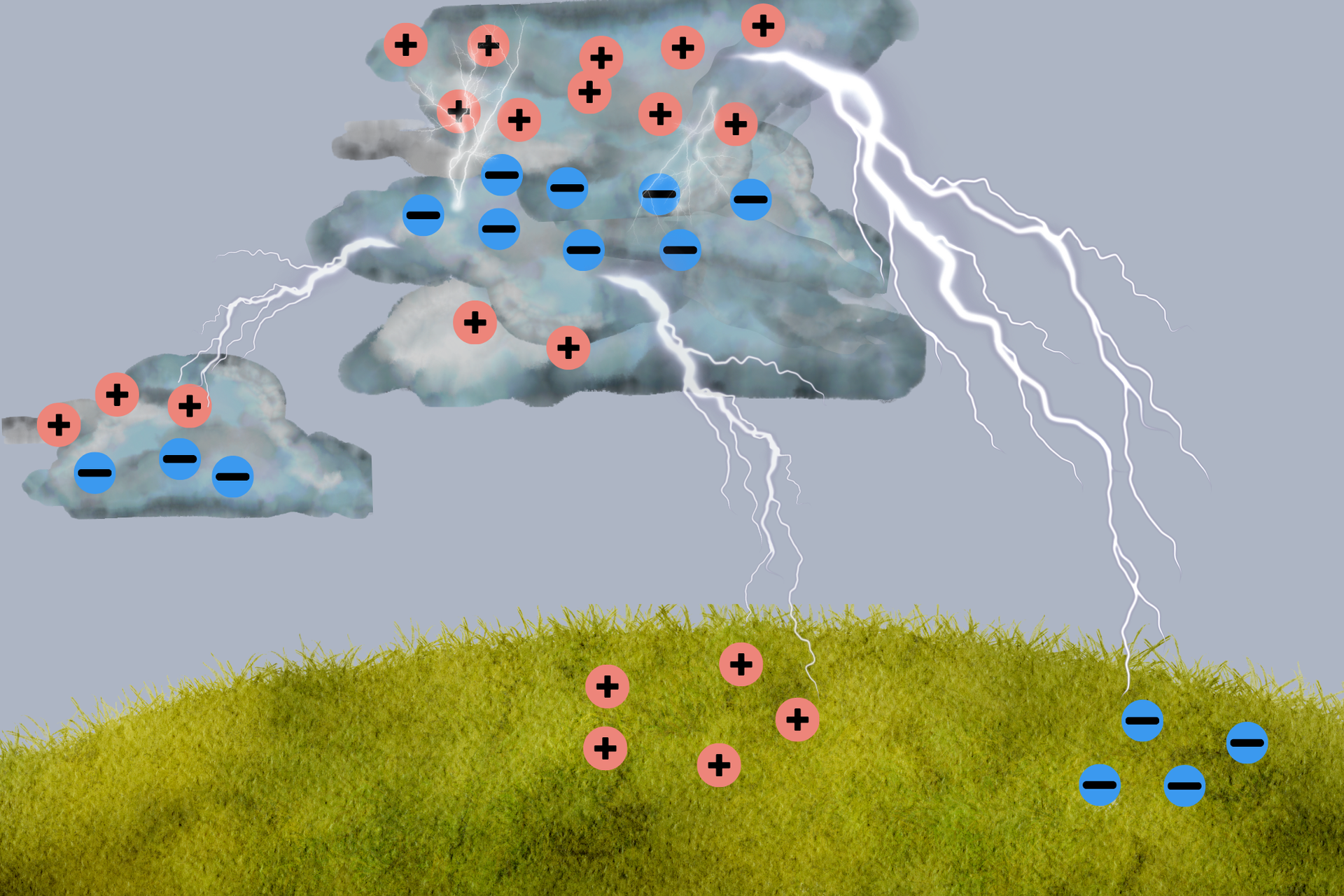

Positive cloud to ground lightning is the most powerful form of lightning but also the rarest. It originates in the positively charged region at the top of storm clouds and travels to negatively charged regions in other clouds or in the ground. “Bolts from the blue” are a type of positive lightning that can travel more than 10 miles horizontally from storms before striking the ground. Positive lightning is also believed to be responsible for many forms of TLEs.

Transient Luminous Events

The existence of visible electrical discharges in the upper atmosphere was first theorized in 1924 by Scottish physicist Charles Thomson Rees Wilson in his article “The Electric Field of a Thundercloud and Some of Its Effects.” Wilson also recorded seeing what modern researchers believe could have been a spirit, a type of TLE. Despite Wilson’s work, the existence of upper atmospheric lightning was not widely accepted until 1989 when researcher R. C. Franz recorded two sprites on a camera that he left recording overnight.

Since sprites were first recorded on camera, interest in upper atmospheric lightning has proliferated in the scientific community and by enthusiasts. This spotlight on the skies has led to the discovery of a slew of captivating electrical events that take place far above thunderstorms.

Sprites

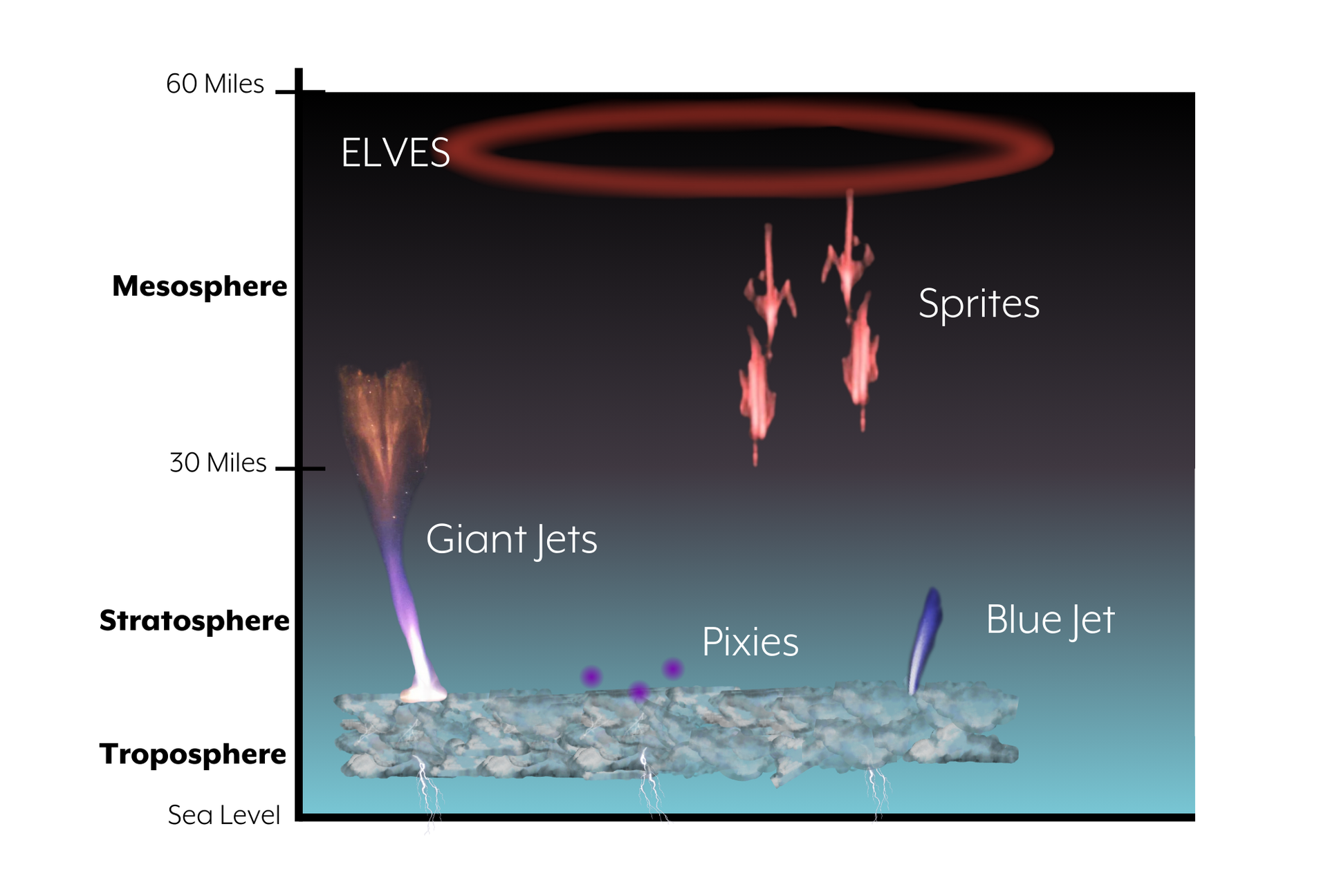

Sprites are the most common and well researched TLE.. Sprites are massive electrical discharges stretching from around thirty-one miles above sea level up to around fifty-six miles. For scale Mt Everest’s summit is five and a half miles above sea level. Sprites are thought to last for only 90-300 ms, meaning that they are very hard to see with the naked eye. They appear red in color with tendrils coming down off a bright glowing area at the top of the formation.

The exact causes of sprites are still debated. Scientists have tied them to positive clouds to ground lightning strikes, as they seem to always occur shortly after these powerful strikes. It is thought that sprites may be caused by the electric field caused by these powerful strikes. Typically, an electric field is not strong enough to turn air from an insulator to a conductor, but at the high altitudes where sprites occur the thin air requires less energy to break down. Currently, further research is being conducted to understand more about the causes of sprites and what impact they may have on atmospheric chemistry including ozone concentrations.

Jets

Jets are TLEs that start at the top of thunderstorms and travel up into the upper atmosphere. There are three types of jets that have been identified: gigantic jets, blue jets, and blue starters. Jets are rarer than sprites and harder to capture on film, and thus we know even less about them.

Blue jets look like quick eruptions of blue light from the top of storm clouds. They are theorized to be caused by breakdown between the positive top of the cloud and the negative “screening layer” that exists above the storm, and if there is enough potential difference between these two areas, then the discharge erupts up past the screening layer.

Blue starters are thought to be like blue jets that do not break through the screening layer. Despite being shorter than blue jets, blue starters are brighter.

Gigantic jets travel up much further than blue jets, reaching altitudes close to 60 miles. One theory of gigantic jet formation suggests that they start as a negative intracloud lightning flash at break out of the top of the cloud.

Elves

ELVES stands for Emission of Light and Very low frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic pulse Sources. ELVES appear as red expanding rings far above storms. ELVES only last for a few milliseconds, so they are impossible to see with your naked eye and very hard to capture on film. Not much is known about what causes ELVES because of how hard they are to observe. They occur at around sixty miles above sea level at the bottom of the ionosphere.

Pixies

Pixies are small pinpoints of light that occur on the top of thunderstorms clouds. They only last about sixteen milliseconds, and their causes are not well understood.

Trolls and Ghosts

Trolls and ghosts are visual components that sometimes occur with sprites. Trolls are trails that appear shortly after sprites going back down to clouds. Ghosts are glowing green spots that sometimes appear at the top of sprites. These names have been given by enthusiasts not scientists, and not much research has been into why sprites sometimes have these elements to them.

The Impacts of Light Pollution

Light pollution happens when people change the amount of light outdoors from its natural level. Light pollution can impact wildlife, human health, and our ability to see the night sky including TLEs. Seeing TLEs requires you to be around 200 -300 miles from a storm with little to no light pollution in between you and the storm. Unfortunately, very few areas like this exist anymore which makes it hard to see TLEs without special equipment or traveling far distances. Paul Smith, renowned TLE photographer, believes that in the days before light pollution sprites and jets would have been much more common to see based on his experience tracking them.

Light pollution can be reduced by shading outdoor lights, using dimmer lights, and turning lights off at night. More information about reducing light pollution is available at

darksky.org

Community Science

If you are interested in learning more about TLEs and potentially seeing them for yourself, NASA has created a community science program for the study of TLEs called

Spiritacular. Observations of TLEs submitted by the community help scientists learn more about what causes TLEs, and what effects they may have. The website has resources on how to find and photograph sprites, elves, and jets, as well as a gallery of photos taken by other citizen scientists. Check out Spiritacular if you are interested in capturing these magnificent events and contributing to our shared understanding of them.

References

DarkSky International. (2024, September 11). DarkSky International.

https://darksky.org/

Lyons, W., Nelson, T., Armstrong, R., Pasko, V., & Stanley, M. (2003). Upward Electrical Discharges From Thunderstorm Tops.

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society,

84(4), 445–454.

https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/84/4/bams-84-4-445.xml

NOAA. (n.d.).

Lightning Basics. National Severe Storm Laboratory. Retrieved November 6, 2024, from

https://www.nssl.noaa.gov/education/svrwx101/lightning/

Preoteasa, G. (2023, February 28).

Chasing Sprites. AMS Weather Band.

https://amsweatherband.org/index.cfm/weatherband/articles/chasing-sprites/

Spritacular. (n.d.).

Spritacular. Spritacular. Retrieved November 6, 2024, from

https://spritacular.org/about

Temming, M. (2024, March 20).

Explainer: Sprites, jets, ELVES and other storm-powered lights. ScienceNewsExplores.

https://www.snexplores.org/article/sprites-jets-elves-storm-powered-lights

Wilson, C. (1924). The Electric Field of a Thundercloud and Some of Its Effects.

Proceedings of the Physical Society of London,

37(1), 32D-37D.

https://web.archive.org/web/20140310135835/http://www.storm-t.iag.usp.br/pub/ACA0330/papers/Wilson_electricfield_thunderstorms_1924.pdf