FIELD NOTES BLOG

All About Mountains

Why Some Mountains are Dormant While Others Aren't

Mountain-building events are a fundamental part of what has shaped the Earth’s topography. Mountains show places where magma plumes exist and places where tectonic plate activity has occurred. When discussing mountains, you may hear the terms “active”, “dormant”, or “extinct”, all of which describe the possibility of that mountain erupting. There are four different types of mountains, they are: dome, fold, fault-block, and volcanic, let's dive into each of these categories, some familiar examples, and what makes a mountain dormant or active.

Dome mountains are rounded and typically asymmetrical. They form when magma rises through the Earth’s crust but doesn’t fully break through its surface. Over time, the lava cools down and turns to rock, resulting in a large circular mound that pushes overlying strata up, also in a circular shape. Over time, this area is prone to erosion. The national monument Half Dome in Yosemite National Park, California, are an example of a dome mountain.

Fold mountains are created where two tectonic plates collide at convergent boundaries, created by intense compressional force, and there are two main types of convergent boundaries. The first is

continental-continental convergence, which is when two continental plates collide and have the same buoyancy so neither of them want to submerge, resulting in upward folding and mountain formation. The second is oceanic-continental convergence, which is when an oceanic plate subducts beneath the continental plate, resulting in sediments and rocks along the exposed edge of the continental plate being compressed and folded, forming a volcanic arc that becomes a mountain. The Rocky Mountains in Colorado are an example of a fold mountain.

Fault-block mountains are formed when underground pressure forces a large crustal rock mass to break away from another and shift along a fault, displacing them from each other; due to tensional stress. Once the crust fractures, some blocks will rise up and others will fall. The uplifted blocks of rock are called horst, and the down-dropped blocks of rock are called graben. The Grand Tetons in Wyoming are an example of a fault-block mountain.

Volcanic mountains are formed by the slow accumulation of erupted lava and pyroclastic material around a volcanic

vent, which piles up around it. Over time the vent grows into a cone-shaped volcano, with the vent at the center. The Aleutian Islands in Alaska are an example of a volcanic mountain.

Mountains are considered active if they have erupted within the Holocene (the current geologic epoch, ~11,700 years) or if they have the potential to erupt again in the future. Mountains are considered dormant if they are potentially active, meaning they aren’t erupting now, but they may erupt in the future. Mountains are considered extinct if there is no longer a connection between the mountain and the magma chamber, meaning they will never erupt again. Instead, they remain as a reminder of how geologically active that area once was. However, sometimes a mountain will be considered extinct for thousands of years but then it will suddenly reawaken. Going extinct doesn’t mean forever like how we are used to, with mountains, extinction can be forever or just temporary. Yellowstone and Long Valley, California are great examples of this; Yellowstone hasn’t erupted in ~70,000 years, and Long Valley hasn’t had recorded activity in ~16,000-17,000 years, making them extinct. However, both of those locations are known to still contain magma within their caldera systems, and they still experience active seismicity, ground deformation, and hydrothermal activity; which makes these mountain systems still active, just currently dormant.

Just because a mountain is active does not mean that the mountain is growing in height and width. Mountains tend to have a maximum size they can grow to before the weight of the materials and rocks is too heavy to support it, resulting in erosion and landslides. How large a mountain will grow is all dependent on the steepness of the slopes, and the rate at which forces are causing Earth’s crust to rise. The tectonic plates are always shifting, each at slightly different amounts but on average they move ~1.5 cm (0.6 in) per year, allowing landforms to be created and destroyed by the movement of the tectonic plates. This process is what constitutes dormant mountains. This gradual movement of plates is what allows for mountains to move away from the part of Earth’s mantle that was actively supplying magma to the mountain, removing the channel that connected the two, cutting off the flow of magma, resulting in this mountain becoming dormant, and a new volcanic arc to begin forming where the vent is now located.

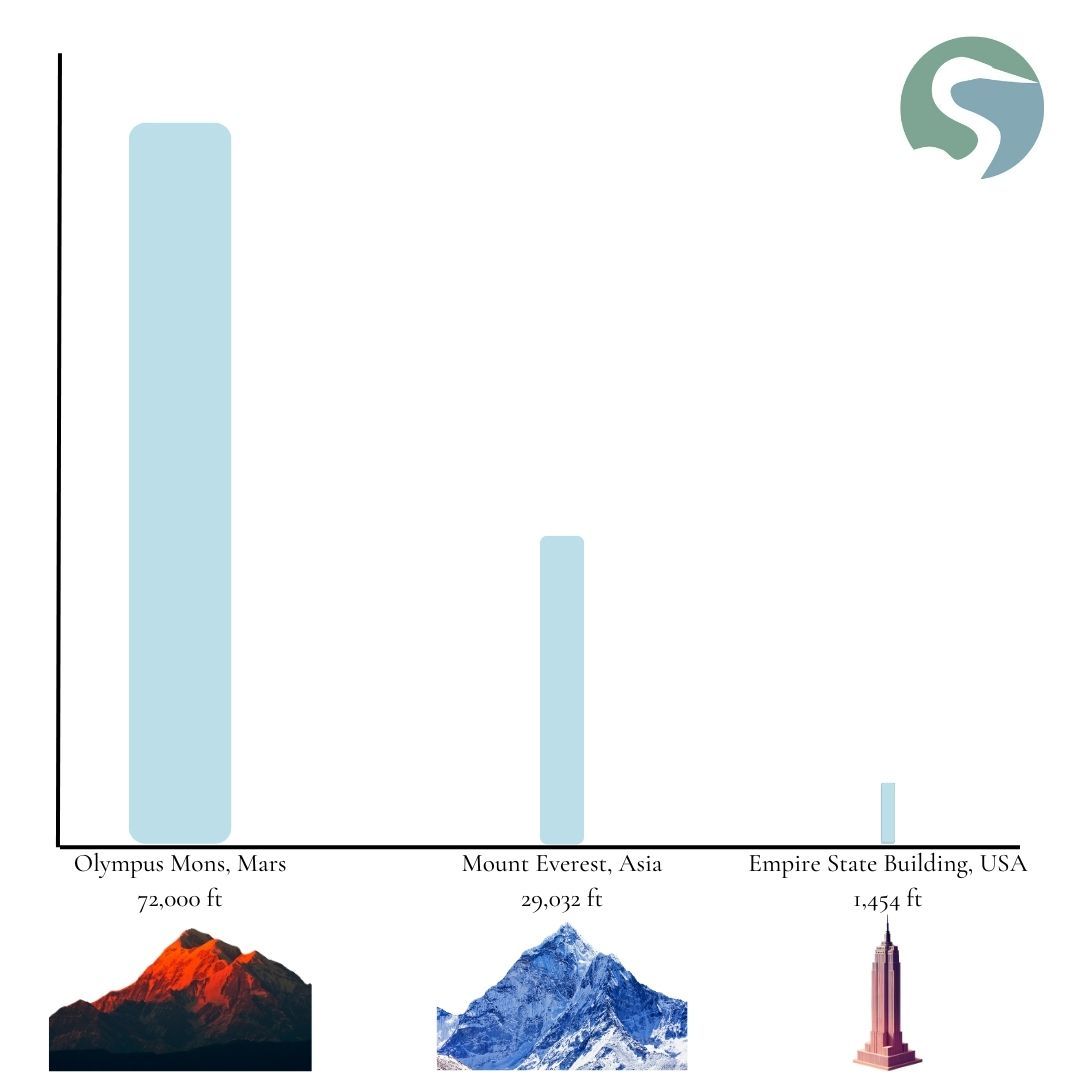

Earth isn’t the only place that has mountains. Mountain-building events also occur on other planets too, Mars, Venus, Pluto, and some moons. However, mountains found outside of Earth are huge in comparison, and this is due to the absence of tectonic plates and the lower surface gravity throughout the solar system. The largest known mountain within our solar system is Olympus Mons on Mars, as it measures ~72,000 feet from base to peak, and it has 6 large calderas inside of the central caldera, measuring 57 miles wide and 2 miles deep. These measurements are almost 2.5 times taller than Mount Everest, which is Earth’s tallest mountain, measuring ~12,000 feet from base to peak. Mars is very interesting because it is the only other planet that has a similar magmatic process, as well as similar igneous rock and mineral types to those found on Earth, but the mountains on Mars are built a little differently than how they are on Earth. Mars doesn’t have tectonic plates, so once a mountain starts building in one area, it will continue to build onto the same mountain until the heat source runs out, which is how Mars has the enormous mountains that we see today. Mars has its own atmosphere and weather conditions, but the rate of weathering and erosion due to these factors is minimal when compared to those on Earth.

Mars doesn’t have tectonic plates, instead, Mars is a very thick piece of crustal rock. However, because the planet is a big piece of rock, it experiences deformation such as periods of shrinking and periods of stretching. These processes and the mountain-building events have caused a few faults to form, one of the most notable being Cerberus Fossae. The Cerberus Fossae are a series of semi-parallel faults and trenches that stretch for more than 1000 km, and activity in these faults causes mars-quakes (Martian equivalent of earthquakes).

Mountains are key indicators that a land mass is active or was at some point in time, and this is true throughout our solar system. Mountains reveal the geologic history of a place as they keep a record of past climates and chemical compositions, and sometimes even preserved fragments of organic matter. All mountains, whether active, dormant, or extinct, are important and unique in their own ways, but the one thing that’s similar is the mountain-building events that formed them.

Sources:

“Fold Mountains: How Do Fold Mountains Form.” Geology In, 30 Oct. 2024, www.geologyin.com/2024/10/fold-mountains-formation-characteristics.html.

Wee, Rolando Y. “The Solar System’s Tallest Mountains.” WorldAtlas, 25 Apr. 2017, www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-solar-system-s-tallest-mountains.html.

“Mars Education: Developing the next Generation of Explorers.” Mars Education | Tectonics, Arizona State University, marsed.asu.edu/mep/tectonics#:~:text=And%20because%20Mars%20has%20no,other%20big%20volcanic%20structures%20nearby.

Anderson, Paul Scott. “Is Mars Volcanically Active?” EarthSky, 3 Nov. 2022, earthsky.org/space/mars-is-volcanically-active-magma-geology-insight/#:~:text=This%20is%20a%20mosaic%20image,still%20existing%20beneath%20the%20surface.

Kohler, Ulrich, and Daniela Tirsch. “Cerberus Fossae on Mars.” Cerberus Fossae - Young Tectonic Fissures Thousands of Kilometers Long on Mars, DLR - German Aerospace Center, 20 Sept. 2018, www.dlr.de/en/latest/news/2018/3/20180920_cerberus-fossae-mars#:~:text=The%20Cerberus%20Fossae%20are%20tectonic,part%20of%20the%20Cerberus%20Fossae.

RECENT ARTICLES