FIELD NOTES BLOG

Herbicide Injuries in Our Natural Areas

“Once you see it you can’t unsee it”

The term “shifting baseline syndrome” was coined by marine biologist Daniel Pauly in 1995 to describe a phenomenon in the study of fisheries in which each generation of researchers took the stock size and diversity at the moment they began their career to be the baseline for their research, and thus the total decline in fisheries around the world since the industrial revolution was not fully appreciated. Since then the term has grown to refer to how people’s understanding of what a healthy ecosystem looks like has declined over time as each new generation has a lower baseline of what is considered a “normal” environment.’ Shifting baseline syndrome can lead to us thinking that things we see in nature are normal when, in fact, they are signs of problems in our environment. As spring progresses, and trees leaf out, you may notice that many leaves appear twisted, cupped, curled or otherwise deformed. While it may seem tempting to think that these deformities are a normal part of leaf formation because that's what leaves have looked like in past years, they are actually a sign of a growing problem in our natural areas– off target herbicide injuries. In this blog we’ll talk about what herbicides are, how they are getting into natural areas, and what the effects are in Illinois ecosystems.

What is an herbicide?

Herbicides are chemicals that are used to kill unwanted plants. They fall under the umbrella of pesticides, which are any chemicals used to kill living things that negatively impact productivity. Controlling weeds has been an important part of agriculture since people started cultivating plants 10,000 years ago. For most of this time, weeds were managed by hand pulling them or “cultural” methods. Cultural methods of weed control are different ways of creating an environment in which desired crops outcompete weeds. These methods can include crop rotation, cover cropping, and soil fertilization. However, in the 1950s everything about agriculture changed in what is called the green revolution. During this time, the invention of the Haber - Bosch process to create ammonium fertilizer from nitrogen gas, and the creation of herbicides allowed for large intensification of agriculture, greatly reducing the need for labor on farms and increasing yields.

Despite the most commonly used herbicides being brought to market between 1945 and 1975, the use of herbicides changed dramatically over time. In the past, herbicides were usually only sprayed preemergence– or before crops came up. However, with the introduction of genetically modified crops that are resistant to certain herbicides, they can be sprayed all growing season, or “over-the-top” of crops.. The most controversial of these has been soybeans that are resistant to 2,4-D and Dicamba, two herbicides that target broadleaf plants and would otherwise kill soybeans. These herbicides are also very prone to vapor drift, which occurs at temperatures over 80°F, meaning that spraying them in the summer drastically increases drift. Dicamba drift made national headlines as it not only affected natural areas but also farmers that weren’t growing resistant soybeans. Dicamba was first approved for over-the-top spraying during the growing season in 2016 by the EPA; however, it lost its approval for this kind of application in 2024 after a district court required the EPA to vacate the approval due to procedural violations.

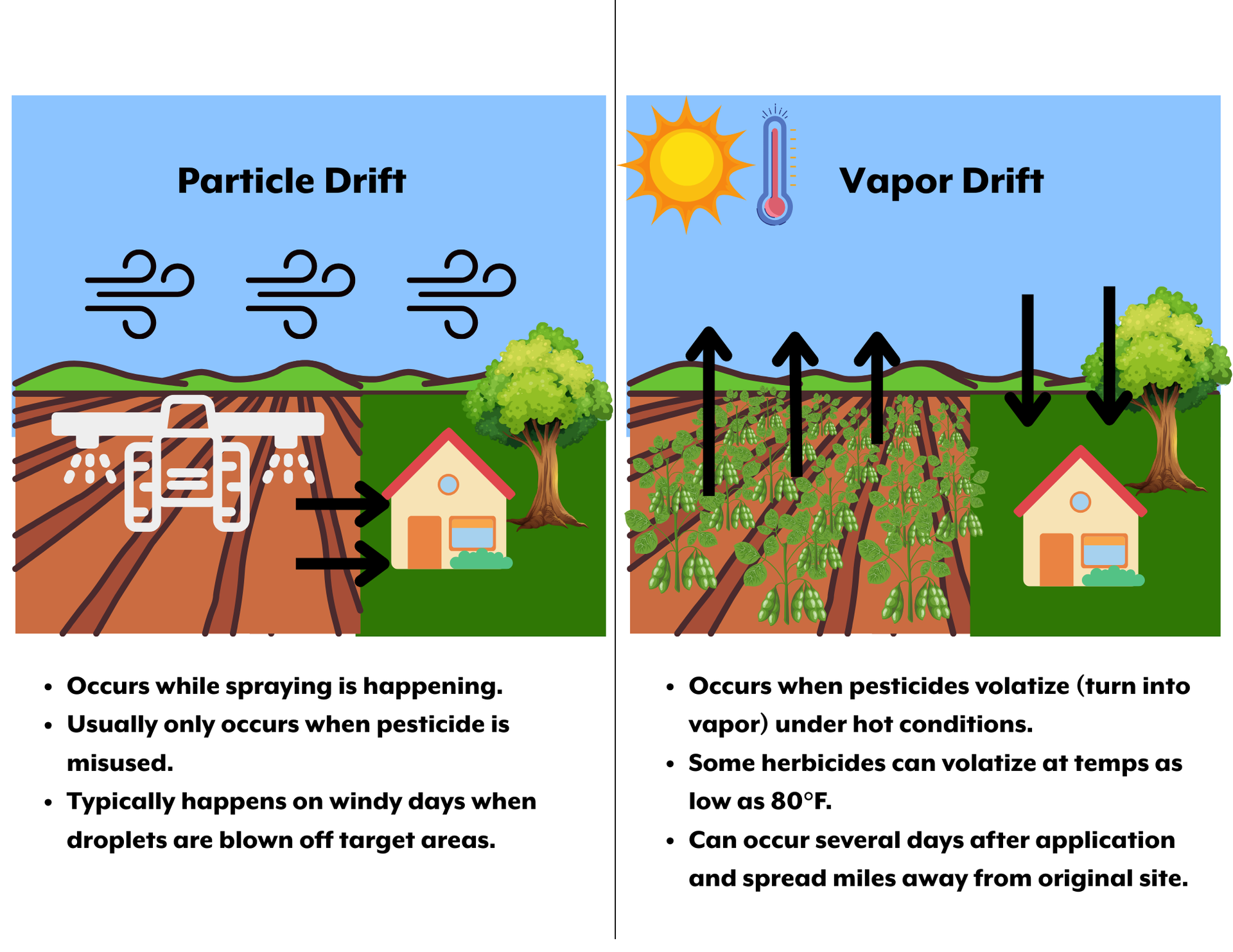

How do herbicides drift?

Herbicide drift refers to herbicides moving from their intended target, usually an agricultural field or lawn, to anywhere they were not intended to be. There are two ways that herbicide drift can occur– particle drift and vapor drift. Particle drift occurs while herbicides are getting sprayed. It usually happens when applicators do not follow the regulations on herbicide labels by applying on windy days or having their sprayers at the wrong height. Vapor drift occurs after herbicides have been applied on hot days. The heat causes herbicides to volatilize, or, turn into a vapor. These vapors can then travel over a mile before being taken up by other plants. Vapor drift can occur even when herbicides are properly applied according to the label and up to 30 days after application. Not all herbicides volatilize at temperatures we normally find in the environment, but two common herbicides, 2,4-D and Dicamba, can volatilize at temperatures as low as 80°F.

Herbicide Injury

Herbicide drift causes direct injuries to plants, and it leads to indirect damage to animals and ecosystems as a whole. Herbicide exposure can cause plants to have deformed leaves, produce fewer flowers, produce fewer fruits and nuts, have lower nutritional contents, cause limb dieback in trees, and even whole plant death in extreme cases. These injuries can have cascading effects across ecosystems, as plants are the basis of the food chain that all other living things rely on. The most visible of symptoms are deformed leaves on trees, making it the best way to identify herbicide exposures apart from sending samples to a lab for testing. Some common deformations are irregular margins, curling/cupping, chlorosis, necrosis, and strapping. Here is what these signs look like:

Chlorosis

Chlorosis refers to the yellowing of leaves as chlorophyll is depleted.

Irregular Margins

Irregular margins refer to the edges of a leaf having a different shape or pattern than they usually do.

Curled or Cupped Leaves

Curling is when the edges of leaves turn down. Cupping is when the edges of leaves turn up.

Necrosis

Necrosis refers to a part or whole leaf dying.

Strapping

Strapping refers to leaves that are longer and narrower than they usually are.

Extent of Herbicide Damage in Illinois

The Illinois Natural History Survey did a study of 185 sites in all counties in 2023. They found at least one pesticide in 74% of the tissues that they tested. They also found herbicide injuries in trees at 99% of the sites that they visited and severe herbicide injuries at 54% of sites. Oaks were the most impacted of any species, which is especially concerning given that oaks are an incredibly important species in Illinois ecosystems. They found that herbicides were much more prevalent prior to July and other pesticides like insecticides and fungicides were much more prevalent after July 18.

While it’s easy to miss the signs of herbicide injury when they’ve become part of our baseline, once you know what to look for— cupped leaves, yellowed veins, jagged margins—it’s impossible to ignore what they mean. It may seem overwhelming to see this damage in ecosystems we once thought of as healthy; however by recognizing herbicide injury for what it is, we can equip ourselves with the knowledge required to push for changes in how and when these chemicals are used, advocate for stronger protections for natural areas, and restore a more accurate baseline of what healthy ecosystems should look like. If you are interested in learning more about herbicide drift Prairie Rivers Network has more resources and a community science monitoring project for herbicide injuries.

Sources:

Benson, T. J., & Zaya, D. (2024). Understanding the extent and consequences of chemical trespass for Illinois ecosystems.

https://dnr.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/dnr/inpc/documents/INHS%20-%20final%20report_.pdf

Erndt-Pitcher, K., & Martin, K. (2024). Hidden in Plain Sight. Prairie Rivers Network. https://prairierivers.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/HerbicideDrift-Report-

Mesnage, R., Székács, A., & Zaller, J. G. (2021). 1 - Herbicides: Brief history, agricultural use, and potential alternatives for weed control. In R. Mesnage & J. G. Zaller

(Eds.), Herbicides (pp. 1–20). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823674-1.00002-X

RECENT ARTICLES