FIELD NOTES BLOG

A Deep Dive into Wildfires

Please note: This blog was originally published by Jillian Neece on August 10, 2023, but has been updated to reflect numbers as of June 2, 2025.

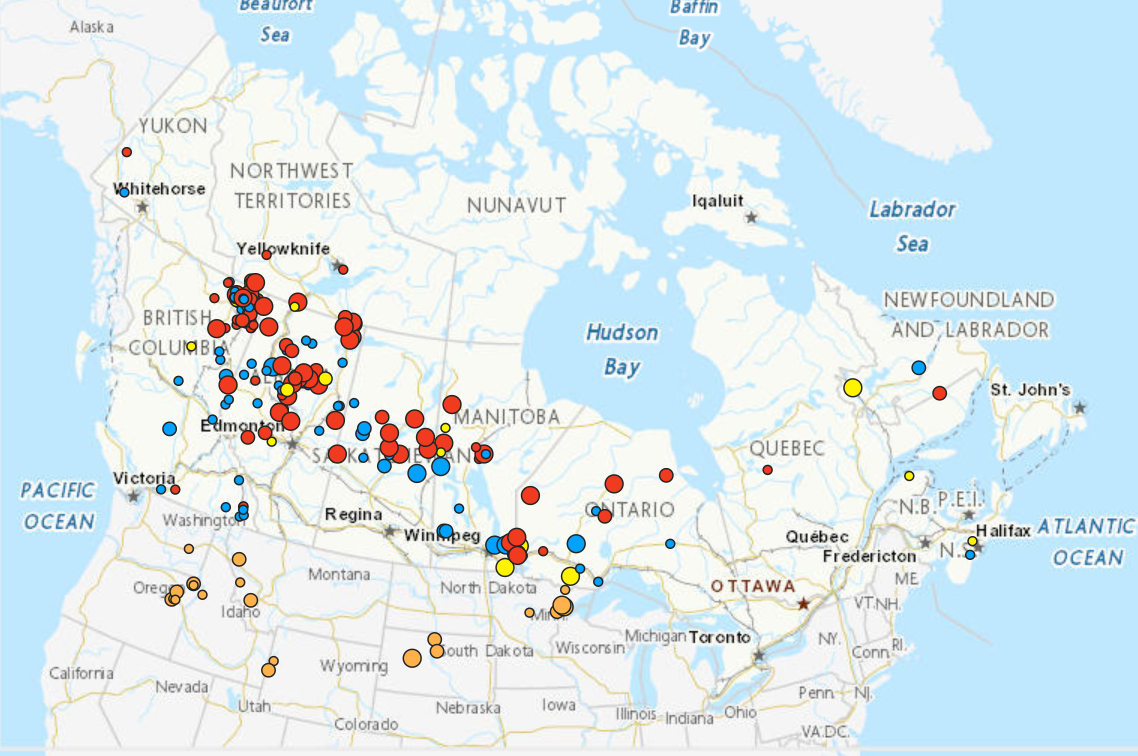

This summer, like every summer at Severson Dells, has been filled with laughing campers, stunning prairie wildflowers, and explorations in the creek. But this summer has also brought record breaking heat and some of the worst air quality the area has ever seen due to wildfires in Canada and the western United States. There are currently 174 active wildfires burning throughout Canada, and 44% of those are considered “out of control.” In the United States, there are currently 7 fires burning throughout 6 states, and only 3 are considered contained. Most experts predict that many of these fires will continue throughout the summer and fall. So, I figured it was time for a deep dive on wildfires!

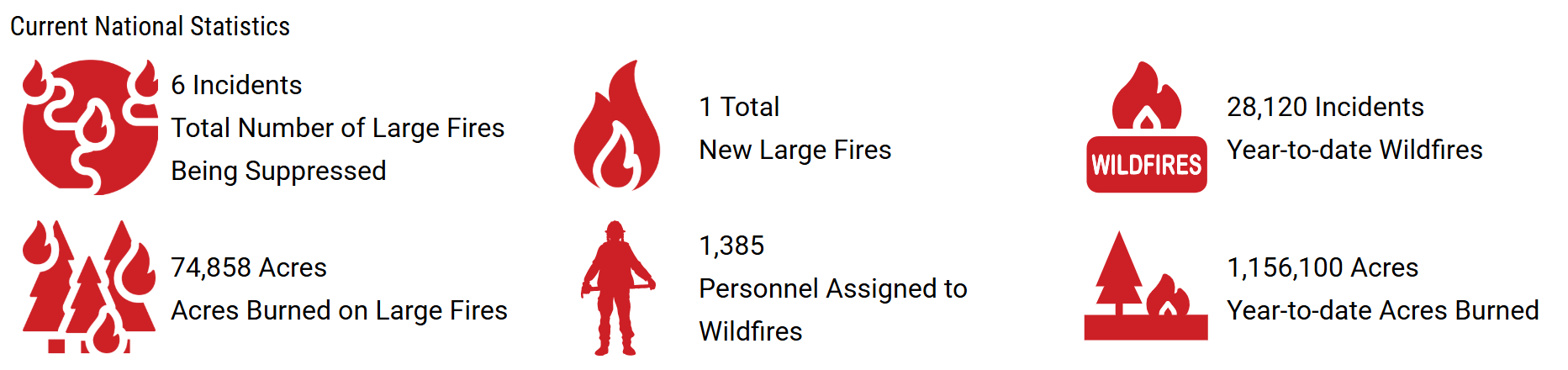

Although only the beginning of June, we can expect these statistics to rise throughout the summer. As a comparison, let's look at 2024. The National Interagency Coordination Center reported that 8,924,884 acres were burned across 64,897 wildfires. Additionally, take a peek at the Active Wildfires in Canada map from August 1, 2024:

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

Wildfires are a complex issue, so there is not a single cause that we can point to as the reason wildfires have become so intense in recent years. Before we can understand our current wildfire situation, we need to look at the history of fire on the landscape. For at least the last 2,000 years (and likely much longer), Indigenous peoples of what is now North America have been intentionally burning areas of forest and grassland for cultural and land management purposes. These burns helped to maintain prairies and savannas that were dominated by grasses and flowers without having to compete with woody shrubs or trees. Additionally, regular forest burns kept tree saplings and woody brush in check, creating a relatively open understory (ground-level) that allowed woodland grasses and flowers, as well as older trees with deep roots and thick bark, to flourish. These relatively non-destructive burning practices lower the frequency of intense wildfires on the landscape while creating resilient, diverse ecosystems.

Now flash forward to the European colonization of Indigenous lands in the western hemisphere. Europeans and their descendants had no experience with intentionally setting fire to the land as a cultural or management practice; instead, they thought fires could only be destructive. Therefore, when Indigenous communities were forcibly removed from their homelands and settlers claimed the lands for themselves, the practice of managing the landscape with fire abruptly ended throughout much of North America. Over time, forests became dense with tree saplings and shrubs, which added a lot more woody biomass to the forest ecosystem. Additionally, dead trees that would have burned periodically during cultural burns built up with forests, adding even more potential wildfire fuel.

A graphic depicting the difference between forests that experience regular burns and those that do not. The “Forest With Regular Burns” graphic shows a few trees, spaced out, and lots of flowering plants in the understory, while the “Forest Without Regular Burns” is densely packed with trees and shrubs, including standing and felled dead trees.

Not only did settlers avoid setting fires to manage landscapes, but they also actively suppressed any naturally occurring fires as quickly as possible. Since they viewed fires as a destructive force in the environment, they aggressively worked to extinguish naturally occurring wildfires, regardless of the risk for human communities or infrastructure. This allowed “fuel” (meaning living or dead woody vegetation and other dry plant material) to reach dangerously high levels that dramatically surpassed historical wildfire fuel levels.

Other changes in land use additionally contribute to the greater intensity of wildfires in the last few decades. Early logging practices of harvesting large stands of healthy, old-growth trees removed many of the fire-tolerant species while leaving only young trees, which greatly lowered the diversity- and therefore resilience- of these areas. The later practice of densely planting large stands of trees of the same age and species created very low diversity areas that were vulnerable to pest and disease outbreaks, which often left acres of unhealthy or dead trees that were the perfect fuel for wildfires. These neatly planted rows of trees also created convenient corridors that allowed fires to spread very rapidly throughout large stands.

To sum things up, the short answer to “How did we get here?” would be: the removal of Indigenous communities from their traditional land stewardship roles led to a massive buildup of wildfire fuel sources. But that isn’t where the story ends.

HOW DOES CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACT WILDFIRES?

Ah, yes. Our old friend, climate change, who always shows up, uninvited, to the party. (I guess if we’re being technical, we did invite climate change to the party through our excessive burning of greenhouse gasses and disregard for natural communities, but somehow we are still shocked and unprepared when she shows up?)

The increased global temperatures resulting from over 150 years of burning fossil fuels has created longer dry seasons and shorter wet seasons throughout the western U.S. This effectively lengthens the fire season by drying out the atmosphere and plants, making it easier for fuel sources to catch. As the area covered by snowpack shrinks with rising temperatures, the area of dry, flammable vegetation will increase. Intense droughts resulting from climate change are also drying up rivers and other bodies of water that may have acted as fire breaks in the past, meaning fires can travel farther and faster.

WHY DO WILDFIRES SEEM MORE DESTRUCTIVE NOW THAN IN THE PAST?

Of course having lots of dry fuel around will make it easier for wildfires to start, but there are other factors that have contributed to recent wildfires being highly damaging in terms of human lives and infrastructure. For one thing, communities and structures tend to overlap more with forested areas than they have in the last 150 years. New roads have allowed people to build houses and communities deeper in the forest. Additionally, expanding suburbs have pushed agricultural lands farther toward natural areas, meaning highly flammable cropland or grazing fields often sit next to dense, dry forests. Essentially, modern communities are much more vulnerable to intense wildfires and structural damage.

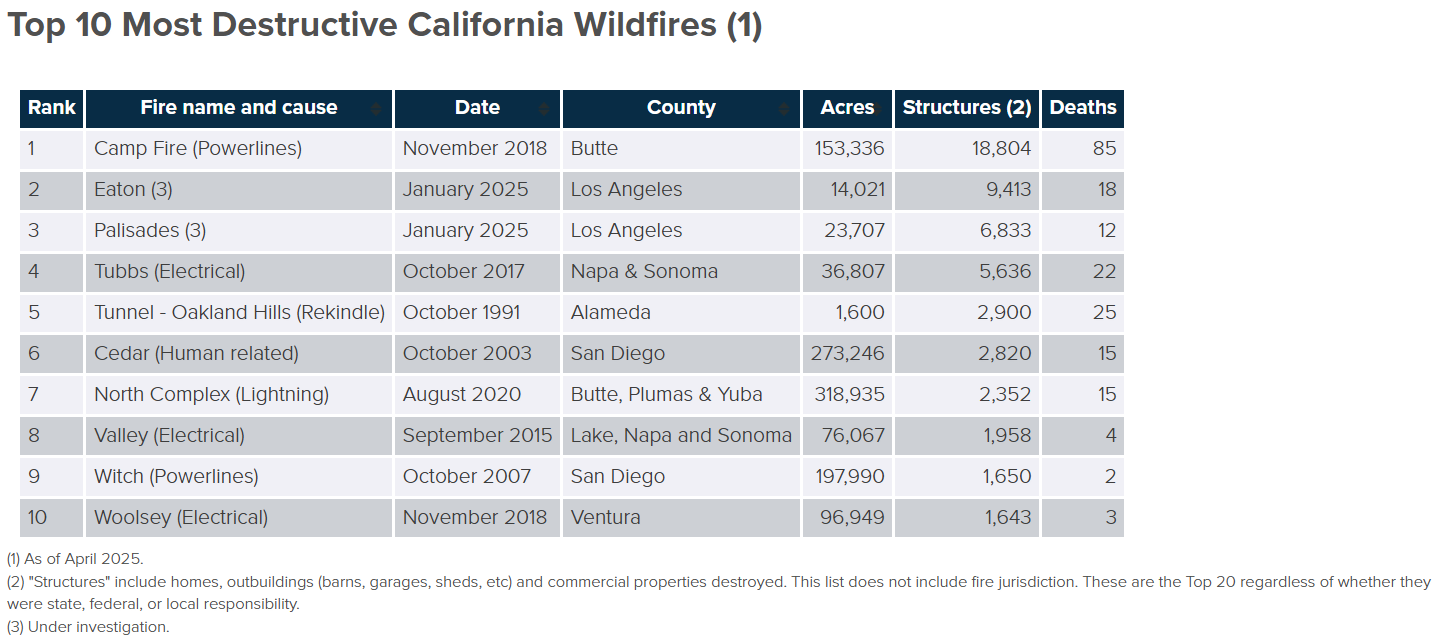

By removing fire from the landscape for so long, we also created dangerous conditions that have made accidental human-ignited fires more common. Over 90% of California wildfires in the last 100 years are thought to be human-caused. As opposed to intentional or prescribed burns, accidental fires are more likely to occur during the hottest, driest, and windiest part of the year, making them incredibly difficult to extinguish. They are also- by definition- going to start near people. Whether ignited by a malfunctioning vehicle, a carelessly disposed of cigarette, or an improperly extinguished campfire, these accidental fires tend to be closer to things like homes and campgrounds, which make them very dangerous and usually cause much more structural damage than naturally ignited wildfires. For example, of the 10 largest wildfires in California history- in terms of acres- 6 were human-ignited, including both intentionally and unintentionally.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR WILDFIRE MANAGEMENT?

Luckily, there is reason for hope! Even though the population of western states has been increasing in recent years, the number of unintentionally ignited wildfires has not been increasing at the same rate. This implies that more people in dry, fire-prone areas does not necessarily mean that accidentally starting forest fires will become more common. Instead, human-caused fires have actually decreased in the last 40 years. Woo!

Additionally, the last 40 years have seen a major shift in the way forests are managed in the United States and Canada. Some land managers are awakening to the wisdom behind Indigenous fire management techniques. For example, the US Forest Service sometimes allows low-intensity natural fires to burn when there isn’t a risk of harming people or communities, which serves as a free way of reducing fuel levels in forests while increasing the diversity and resilience of these areas. In other areas, intentionally lit, low-severity fires have been reintroduced into ecosystems with the goal of returning forests to a more historically accurate and fire-resilient state. I highly recommend checking out the College of Menominee Nation’s Sustainable Development Institute for resources about integrating Native values with forest management.

Beyond adopting Indigenous land management practices, some natural areas have been returned to Indigenous communities. This allows them to bring traditional management techniques back to the landscape while revitalizing their own language, Indigenous sciences, and cultural practices that federal and state governments tried to deprive them of for most of the 19th and 20th centuries. Recent examples of this include the

Esselen tribe purchasing a 1200 acre ranch in Northern California, the Kalispel Tribe of Indians using internal funding and a grant from the USDA’s Community Forest Program to purchase 350 acres of forest, and a nonprofit in Washington state handing over 328 acres of forest and salmon spawning ground to the

Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Indigenous Peoples from across the globe have

the best track record of protecting and managing lands, so it makes sense that having more land under Native management would be beneficial for ecosystem health and resilience in the face of wildfires.

WHAT CAN I DO?

It can be easy to feel hopeless or overwhelmed about your ability to have an impact on something as complex as wildfires, but there are always things you can do. If you are really dedicated to combating ongoing and potential future wildfires, you could apply to join a wildland firefighting team through the Department of the Interior or the US Forest Service (they are always hiring!). If directly fighting fires isn’t your thing (it definitely isn’t mine!), you could support land restoration programs in your area that remove woody brush in forest understories. Alternatively, you can vocally and financially support efforts to return lands to Indigenous management. Try using https://native-land.ca/ to see who’s traditional lands you inhabit, and see if any of them have a land reclamation fund that you can donate to. Finally, and hopefully most obviously, be mindful of burn bans and always be responsible with flammable materials. We want to reintroduce fire to the landscape, but not by accident! Maybe instead of Smokey the Bear’s “Only YOU can prevent forest fires,” the slogan should be “We can co-exist with and use fire to steward a resilient landscape!”

Main ideas adapted from: https://www.publish.csiro.au/wf/pdf/WF22155

Canadian Forest Service. 2022. Canadian Wildland Fire Information System (CWFIS), Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Northern Forestry Centre, Edmonton, Alberta. http://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca.

Please note: This blog was originally published by Jillian Neece on August 10, 2023, but has been updated to reflect numbers as of June 2, 2025.

RECENT ARTICLES