FIELD NOTES BLOG

Composting 101

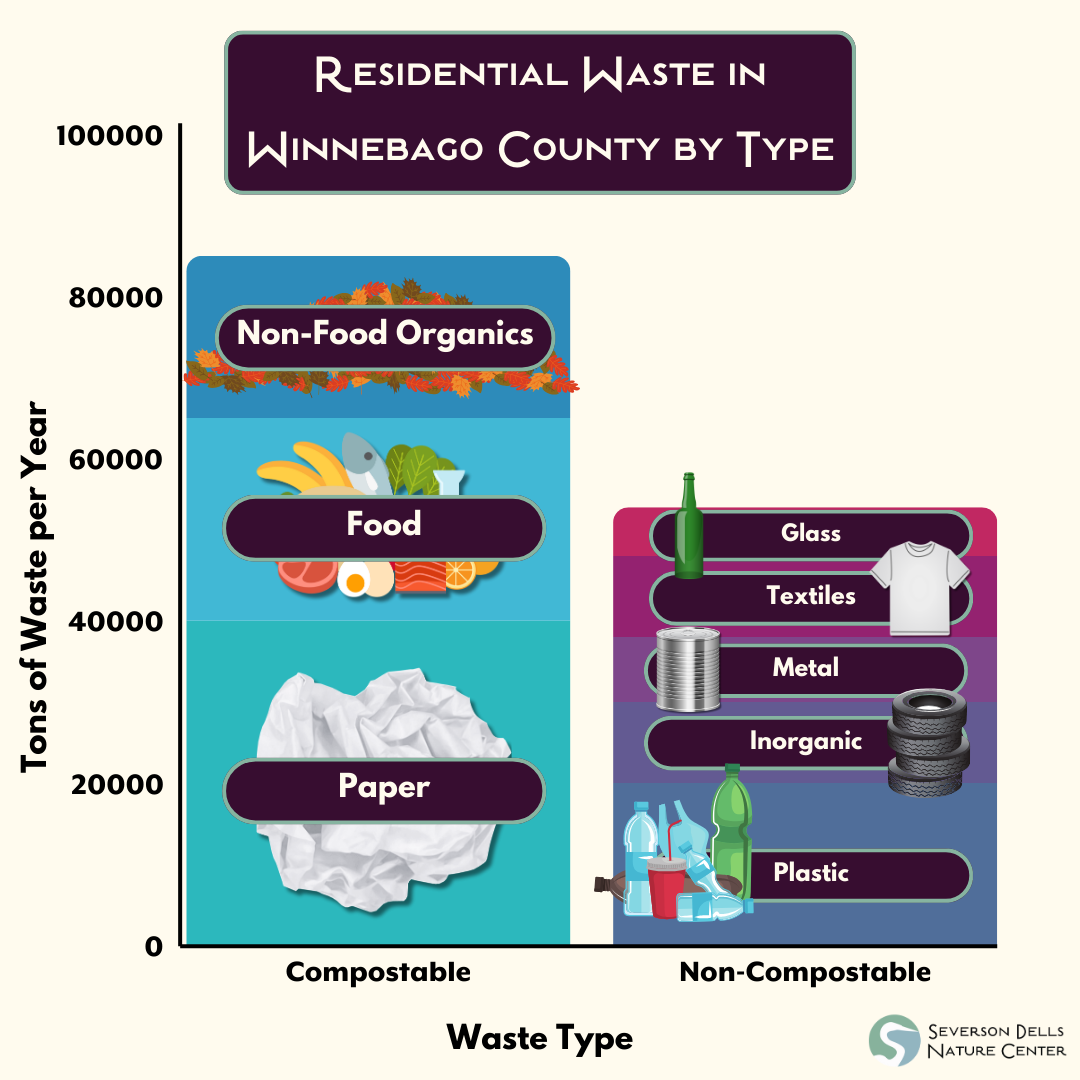

It is the worst-kept secret that we are making too much waste. The two main landfills that Winnebago County uses, Orchard Hills and Winnebago, have life expectancies of six and sixteen years respectively. There are currently no plans to expand these landfills, which is a process that can take around twenty years. This means that it is on us to reduce the amount of waste we are sending to our landfills before they fill up. Around 60% of the residential waste that is produced in Winnebago County is organic waste, which means that it comes from something that was once alive. Thankfully, nature has a way of recycling organic waste that we can learn from. It's called composting!

Composting is the process of turning organic material into fertile soil. Composting works by balancing the inputs and altering the conditions of a compost pile to promote the growth of certain types of organisms called decomposers. There are two types of decomposers: physical decomposers and chemical decomposers. Physical decomposers are animals like worms and millipedes that break down dead material by grinding or chewing. Chemical decomposers are bacteria that produce chemicals to break down small organic matter into even simpler components.

The process of composting involves controlling the conditions of the pile to select what decomposers are present. Creating compost is all about balance, and there are two main factors that must be balanced in order to make compost: the ratio of carbon to nitrogen and the ratio and the amount of air and water.

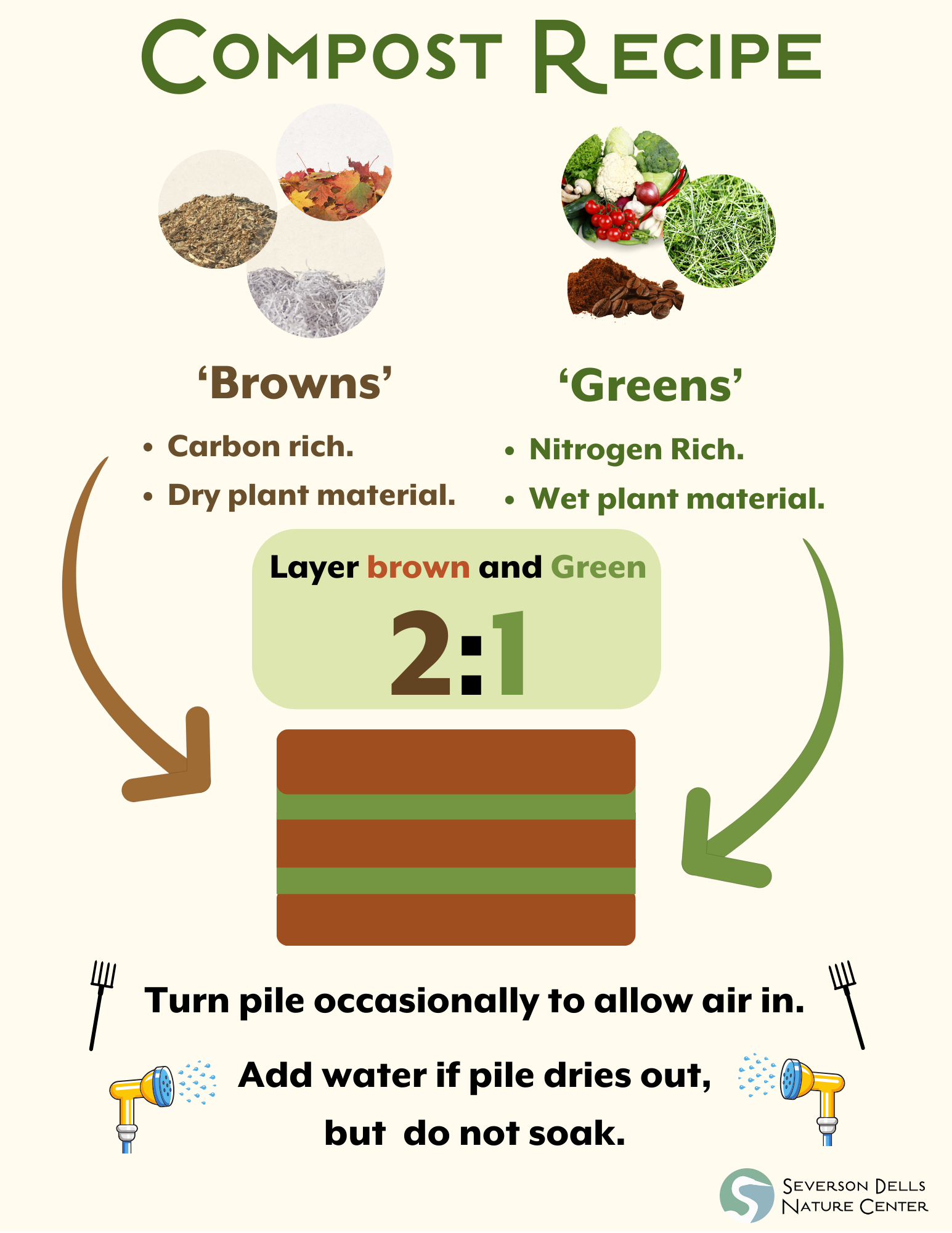

All living things contain both carbon and nitrogen which means that all dead things do too. However, different compostable materials contain different ratios of carbon to nitrogen. “Browns,” for example, are carbon rich with a roughly 50:1 ratio of carbon to nitrogen. Browns are dry plant material that has been usually dead for longer, including dead leaves, straw, woodchips, and even paper. “Greens”have a much higher portion of nitrogen than browns with only about a 15:1 carbon to nitrogen ratio. Greens include plant material that was alive a lot more recently like vegetables, grass clippings, and coffee grounds. Using roughly twice the amount of Browns to Greens by weight will produce an optimal ratio of carbon to nitrogen for the decomposers to flourish and make the finished product a great fertilizer for plants. In most home composting setups meat can not be composted because the pile does not get hot enough and it can attract large animals; however, some large scale composting techniques can be used to compost meat.

It is very important to create a balance between air and water in the compost pile to ensure that the compost pile has the right kind of decomposers. Bacteria can be grouped based on if they need oxygen to breathe or not. Bacteria that need oxygen are called aerobic and ones that do not need oxygen are called anaerobic. Aerobic environments are favored for compost because aerobic bacteria break down organic matter faster and don’t do not produce odorous gasses like methane. In order to create an aerobic environment, it is important to occasionally turn a compost pile over to make sure it is loose enough to let air in. It is also important to find a sweet spot between too wet and too dry. The bacteria need moisture because water is required in cellular respiration. However, if there is too much water, it can create an anaerobic environment.

Composting benefits our environment in numerous ways when compared to landfill disposal. Composting has lower greenhouse gas emission, it has less odor, and it reduces our dependence on synthetic fertilizers. Landfills create around 15% of all human caused methane emissions. Methane is a greenhouse gas that is the second largest contributor to climate change. It is created in landfills by anaerobic bacteria called methanogens that produce methane as a byproduct of decomposition of organic matter that could be composted.

Anaerobic bacteria are also responsible for the bad odors associated with landfills and garbage. Sulfate reducing bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide as a byproduct of decomposition, which is the gas responsible for the rotten egg smell. While these odors do not have direct negative health impacts that we know of, they can have indirect health impacts by causing immense stress, nausea, and lack of sleep that can greatly increase your risk of other health disorders. The aerobic bacteria in compost do not produce these gasses and thus it does not smell bad!

The best benefit of composting is that it creates an organic fertilizer that can be used in gardens and on farms. Producing compost reduces our dependence on synthetic fertilizers that cause environmental problems like eutrophication in wetlands, lakes, ponds, streams, and oceans.Composting is an essential part of natural farming and has been used for thousands of years.

Composting your organic household waste can be easy if you have the time and space; however, a lot of us don't have the space, time, or energy to set up a compost pile. This is where community composting organizations can help. The organizations collect people’s compostable waste and turn into compost at a larger scale. Here at Severson Dells, we have recently partnered with a new community composting organization right here in Rockford called Nettle Curbside compost. Nettle comes and picks up the food scraps from our field trips and other events like Golden Hour in the Grove that produce too much food waste for us to compost ourselves. Nettle even offers curbside compost pickup for household residences! If you are in the Rockford area looking for a way to lower your carbon footprint and send less to the landfill, check out our friends at Nettle to see if they can take your waste and turn it into soil.

https://www.nettlecompost.com/

Sources:

https://www.globalmethane.org/documents/gmi-mitigation-factsheet.pdf

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/landfill/html/ch3.html

https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/composting