FIELD NOTES BLOG

Plant Migration and Climate Change

What do you picture when you hear the word ‘migration’?

For me, it brings to mind the image (and sounds) of geese flying south for the winter or monarch butterflies covering trees in California and Central Mexico. On the surface, migration can be a pretty straightforward concept: when conditions become unfavorable, you move somewhere else. But it becomes a lot more difficult- both to imagine and to enact- when movement isn’t an option. And yet, it still happens!

One of the fundamental characteristics of plants is that they are not capable of moving around like animals are. Sure, they can direct their growth to find the sunniest spot in the area, but overall, where they are is where they’ll stay. So in the context of plants, migration has a bit of a different meaning. Rather than denoting the movement of individuals to a different location, plant migration refers to the shifting of plant distributions over time. One individual plant cannot migrate, but over multiple generations, the range of places where we can find certain plants can change.

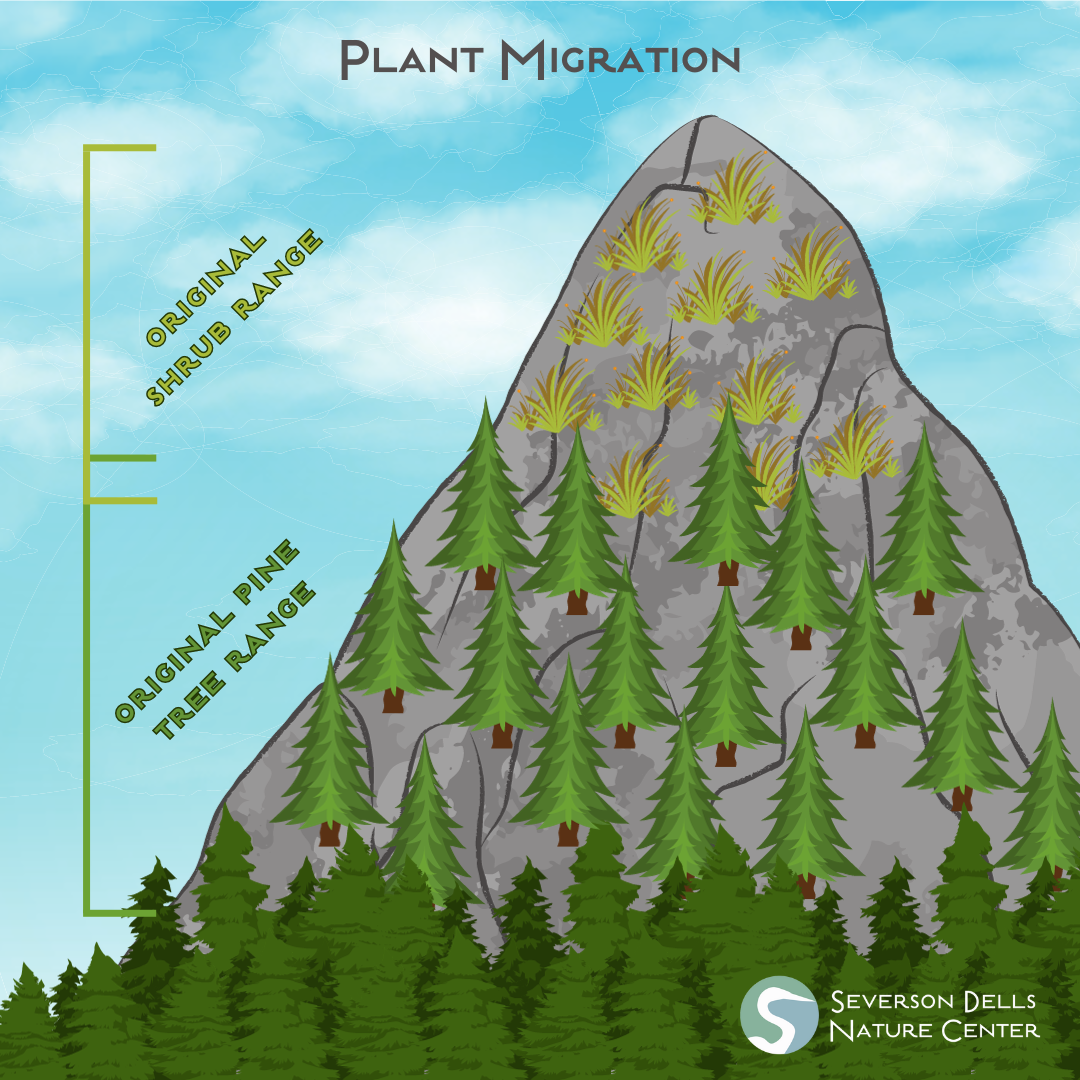

A hypothetical depiction of plant migration. The pine species grows only where the forest line stops, but not all the way to the mountain peak. The shrub only grows from the peak to the place where pines stop growing.

The easiest way to imagine this is to picture a mountain. As the altitude increases, the average temperature and precipitation will change, meaning different plant species will thrive in different places along the mountain. Maybe a certain pine tree doesn’t grow well with other trees, but it’s able to survive colder temperatures, so they can grow a little higher up the mountain. Once the altitude gets too high though, the air gets too cold for them too, and they can’t keep spreading upwards. Instead, maybe a shrub species is well adapted to the cold at the mountain peak, but they don’t do well if they get shaded out by pine trees. That situation might look something like this:

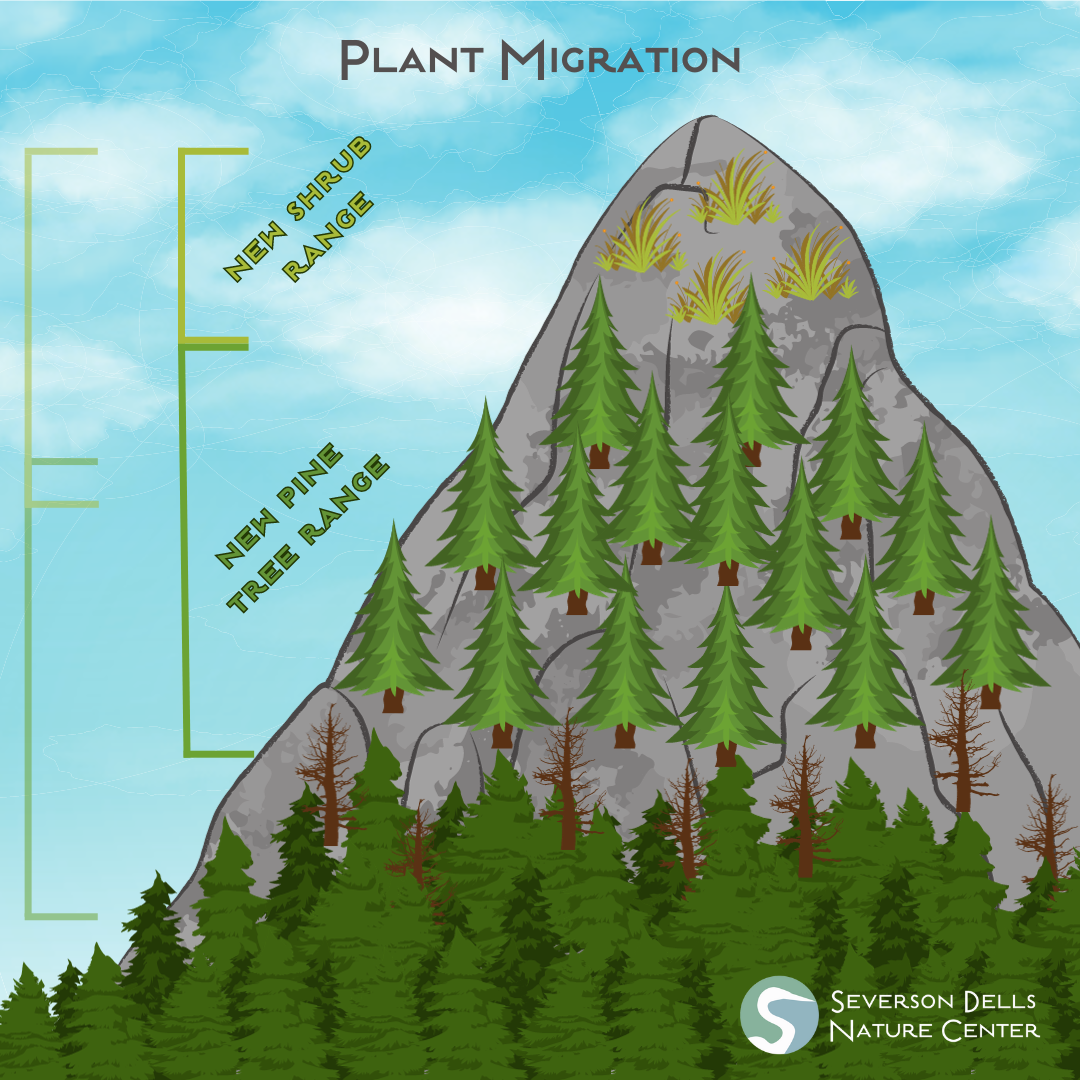

After being exposed to warmer temperatures, the forest line and the pine species are able to grow at higher altitutes, pushing the shrub species into a smaller area. The total pine range stayed about the same, but shifted up the mountain, while the shrub range shrunk.

Now imagine that this mountain exists on Earth during 2023, in a time of rapidly changing climate. As temperatures increase, the trees won’t be as limited by the cold, so both the pine trees and the other trees will be able to grow a little farther up the mountain. This is great for the pine trees because they have plenty of room to expand upwards, but it’s bad news for the shrubs. Now that the pines are growing at higher altitudes, the shrubs don’t have access to all the sunlight they need. And since they are already living at the peak of the mountain, there is nowhere they can go to expand their population. Now the situation looks more like this:

As the pine species migrated higher up the mountain, it created an environment that isn’t as suitable for the shrub. Without the ability to migrate to a more favorable habitat, the shrub’s distribution will shrink and their population on the mountain will decline. The process of plant migration doesn’t just occur at high altitudes; it is happening constantly in ecosystems across the world.

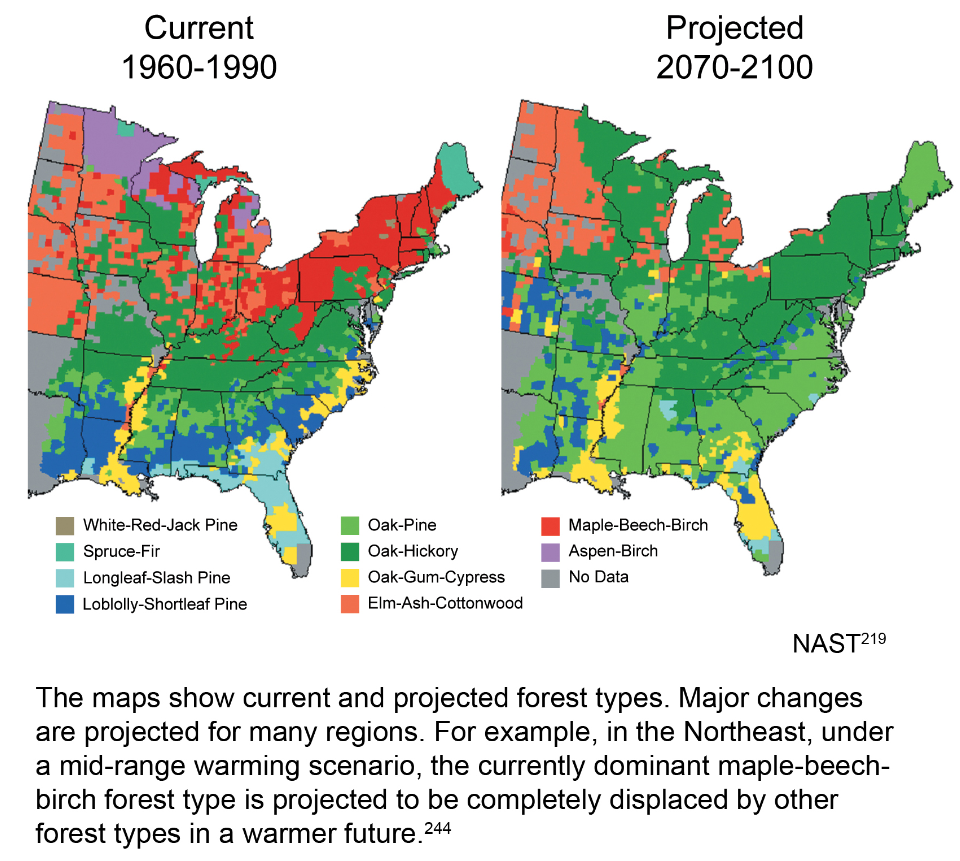

Graph from: USEPA Climate Change impacts on forests

Climate change is a major driver of plant migrations. Obviously warmer temperatures will allow cold-intolerant tropical plants to expand farther from the equator, but there are more subtle examples as well. Rising sea levels will give plants like seaweed and mangroves an opportunity to migrate inland, while simultaneously pushing back coastal plant communities. Here in the midwest, climate scientists predict that our summers will become hotter and dryer while our winters and springs will become a little warmer and a lot wetter. This could mean trouble for plants that need a lot of moisture in the summer while creating the perfect conditions for highly competitive and drought-tolerant invasive species to take over new areas. On top of that, habitat fragmentation has made it more difficult for plant species to spread their seeds to suitable new habitats.

Luckily, researchers are finding ways to help. Creating ‘ buffer zones ’ around natural areas gives nature a little extra wiggle room for plants to expand or shift their distributions. Additionally, habitat corridors- strips of natural areas that connect several larger natural areas- can combat habitat fragmentation and provide the stepping stone that plant and animal species need to access the resources in a different location.

Without the ability to pick themselves up and move somewhere else, plants have to rely on a “migrate or acclimate” policy for dealing with environmental changes. But with the climate changing so quickly, many plants won’t be able to acclimate quickly enough to survive , leaving migration as the best- and sometimes only- option.

RECENT ARTICLES