FIELD NOTES BLOG

Endangered Species Act turns 50!

This December will mark the 50th anniversary of the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) being enacted into law. It is considered one of the strongest pieces of conservation legislation, and since it was passed into law in 1973, it has kept an estimated 99% of listed species from going extinct. So in honor of the ESA’s 50th birthday, let’s take some time to appreciate its history and many success stories, while still recognizing the aspects of conservation legislation that still have some opportunities for growth.

Overview

The Endangered Species Act did not arise in a vacuum. Rather, it was just one of many environmental laws passed during the height of the 20th century environmental movement. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, people were becoming more aware of the impact they were having on the Earth and its ecosystems. The publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, the oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara in 1969, and the first photographs of Earth from space brought to public attention the reality that our planet is a a closed system and the actions we take and the pollutants we emit have a direct impact on ourselves and our environment.

some Endangered species from Illinois.

The Endangered Species Act also built upon previous bills. The 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act allowed the government to create a list of endangered species and authorized limited protections for them. Three years later, the Endangered Species Conservation Act included protections for worldwide species at risk of extinction, which explains why only about half of the species listed under the United State’s Endangered Species Act are actually native to the US.

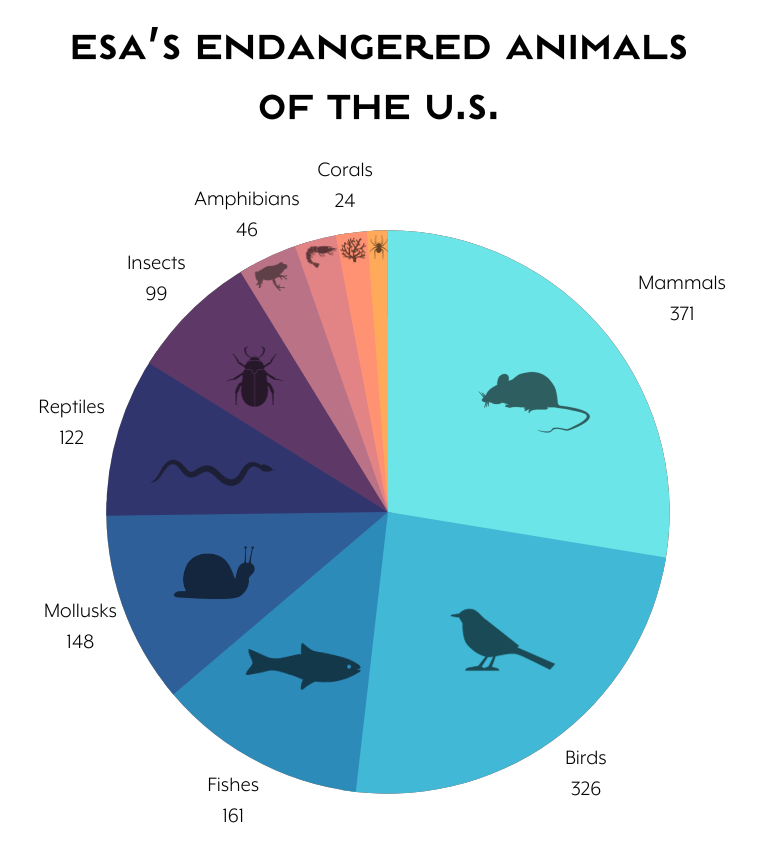

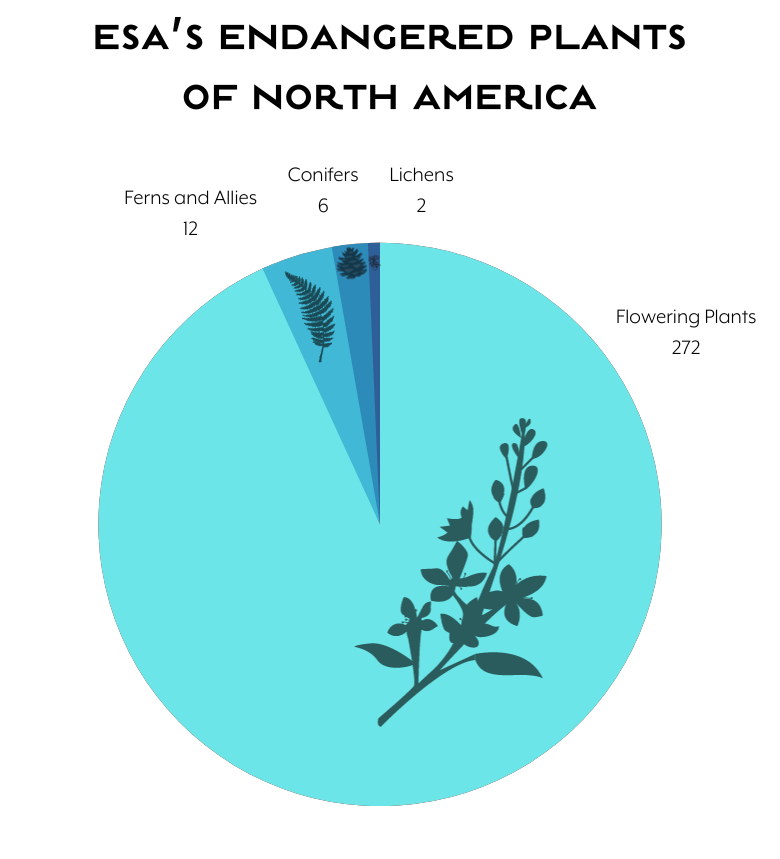

What made the ESA unique was its official definition of ‘endangered’ and ‘threatened’ species and the proclamation that federal agencies could not fund or participate in any activity that would threaten any of the listed species. The ESA outlines how federal agencies and states would cooperate to enact the law, while also expanding what could be listed as endangered to include plants and invertebrates like insects and mollusks.

Going beyond protecting individual species, the ESA can also recognize ‘critical habitat’ for listed species, which would be areas in their environment that these species depend on for survival. Once a habitat is listed as ‘critical habitat’, any project that threatens to disturb the area has to go through an extra permitting process if a federal agency is involved. It does not, however, mean that the habitat is preserved as a sanctuary or that any disturbance is prohibited. Any project that does not include federal funding or involve a federal agency is still free to legally damage critical habitat without any additional permitting. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service (who oversees the Endangered Species Act), the purpose of designating an area as critical habitat is to ensure that other federal agencies do their due diligence by consulting with USFWS before taking any action that could unintentionally harm endangered species.

In the 50 years since its adoption, the Endangered Species Act has given us a lot to celebrate. From the locally relevant Bald Eagle ( delisted in 2007 , recovered) and Peregrine Falcon ( delisted in 1999 , recovered) to the more distant humpback whales (several populations delisted in 2016) and tigers (still endangered, but wild populations are beginning to increase), the protections that the ESA provides to at-risk species- including banning wildlife trade, drawing attention to harmful chemicals, and increasing funding options- has had a significant impact on the health of these populations.

ESA Looking Forward

While the Endangered Species Act has been mostly successful in preventing species extinction, there is still plenty of room for improvement that could lead to better protection for at-risk species. For one thing, getting a species listed as federally endangered takes an average of 12 years. This is 10 years longer than the process is supposed to take, and some experts believe that this delay has led to at least 47 species going extinct while waiting to be listed.

Additionally, in order for a species to be listed, there has to be a lot of evidence that its population is rapidly declining. This means that not only do we need a lot of modern data on that species, but we also need a lot of reliable data from previous decades to compare the modern data to. For species that are recently described or difficult to research, this can mean that sufficient data isn’t available to have them listed, no matter how at risk the population actually is.

Protecting species from extinction also required a significant amount of funding and research. When a species is listed as endangered, a recovery proposal is submitted outlining the steps that need to be taken to protect it, including a proposed budget for taking those steps. It is estimated that current overall funding for species protection is only about 3% of what these recovery plans say is necessary to bring these species back to healthy population levels.

Another limitation of the Endangered Species Act as it was written is the lack of protection for habitats and ecosystems. While the ‘critical habitat’ designation recognizes some of these ecosystems as important to preserving biodiversity, it does not actually preserve those areas. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which manages the globally comprehensive Red List of endangered species, has also created a Red List of Ecosystems that ranks entire ecosystems on a scale of Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, and Collapsed. According to their list, for which data is still being gathered, the US has at least 20 ecosystems that are considered threatened (meaning they are listed as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered). Since the US does not have any legislation that protects biodiversity at the ecosystem level, however, the habitats as a whole do not receive any federal protection.

Back in 1973, the writers of the Endangered Species Act could never have imagined the obstacles facing species today. From habitat loss and toxic chemicals to climate change and disease, surviving in the modern environment is proving to be an uphill battle for many plants, animals, fungi, and ecosystems. Luckily we have the ESA to look to as a model and jumping off point for future legislation to conserve and support biodiversity in the US.

RECENT ARTICLES