FIELD NOTES BLOG

Defining Seasons

Defining Seasons

Now that winter has arrived in full force, I’m sure many people are wondering when warmer temperatures will be gracing us with their presence again. Don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of fun outdoor activities to enjoy in the winter like sledding, skiing, and winter hiking, but when temperatures are as cold as they have been, I can’t help but look forward to spring. That led me to wonder: When does spring officially start? After doing some research, I realized that the answer is not as straightforward as it might seem.

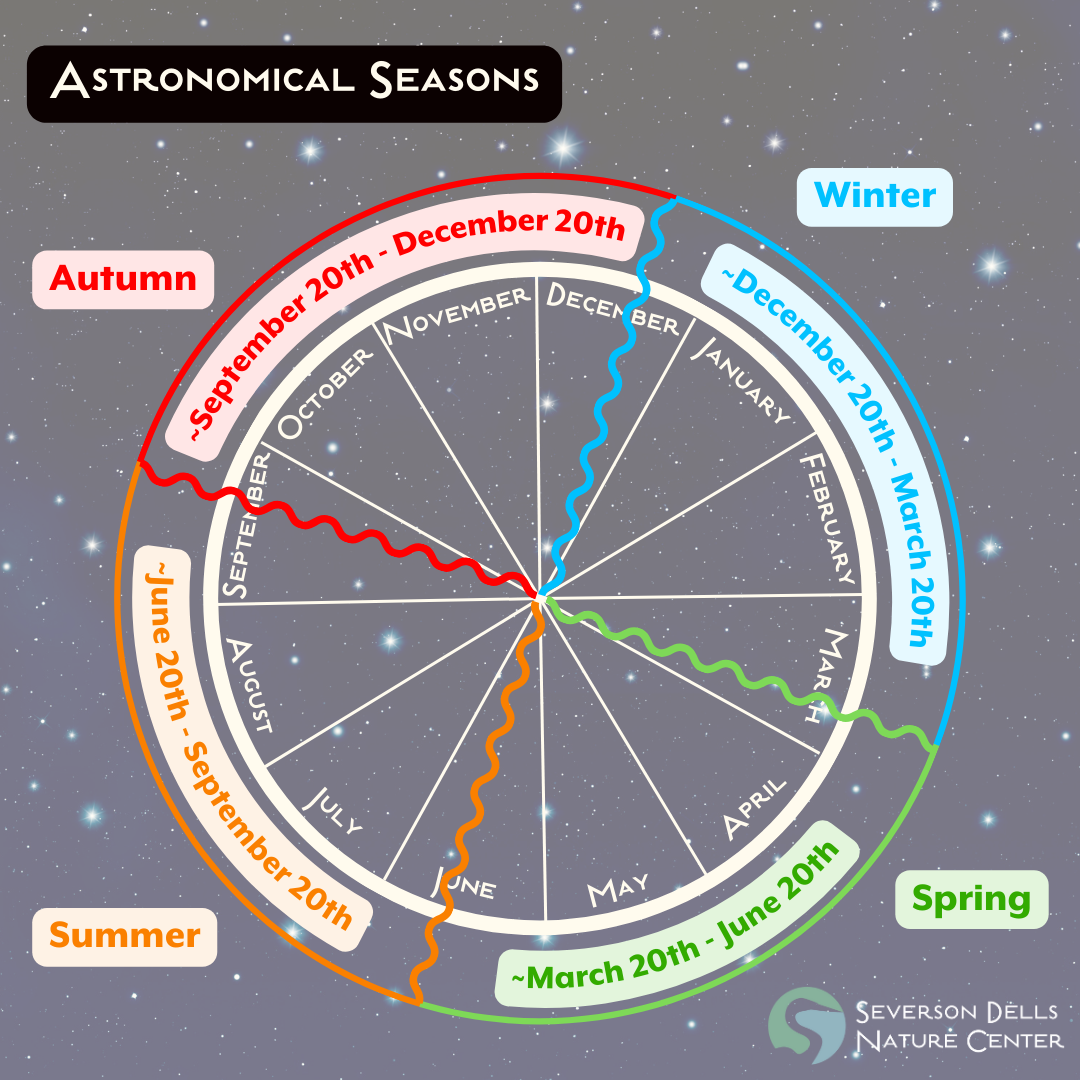

Seasons can be tricky because there are two popular ways of defining them: the astronomical way and the meteorological way. Astronomical seasons (think astronomy; the movement of planets) are distinguished based on where the Earth is on its orbit around the sun. This method uses the dates of equinoxes (when day and night are equal lengths) and solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year) as transitions between the four seasons. Any time after the winter solstice (December 21st or 22nd) but before the spring equinox (March 19th, 20th, or 21st) is considered winter, and so on.

using the astronomical definition, each season begins with a solstice or equinox, meaning the calendar date of the season’s beginning may vary each year.

Since the Earth’s orbit around the sun is not a perfect circle, there is some variation in the length of the seasons and on which calendar day the seasons will begin. This can make it difficult for scientists and weather forecasters to compare weather and climate information between different years. Weather from some day in 1990 might not actually be comparable to that same calendar date in 2024 if the Earth was in a slightly different place in its orbit. Thus we needed a different way to track the seasons that is more relevant to our human activities. Enter: meteorological seasons!

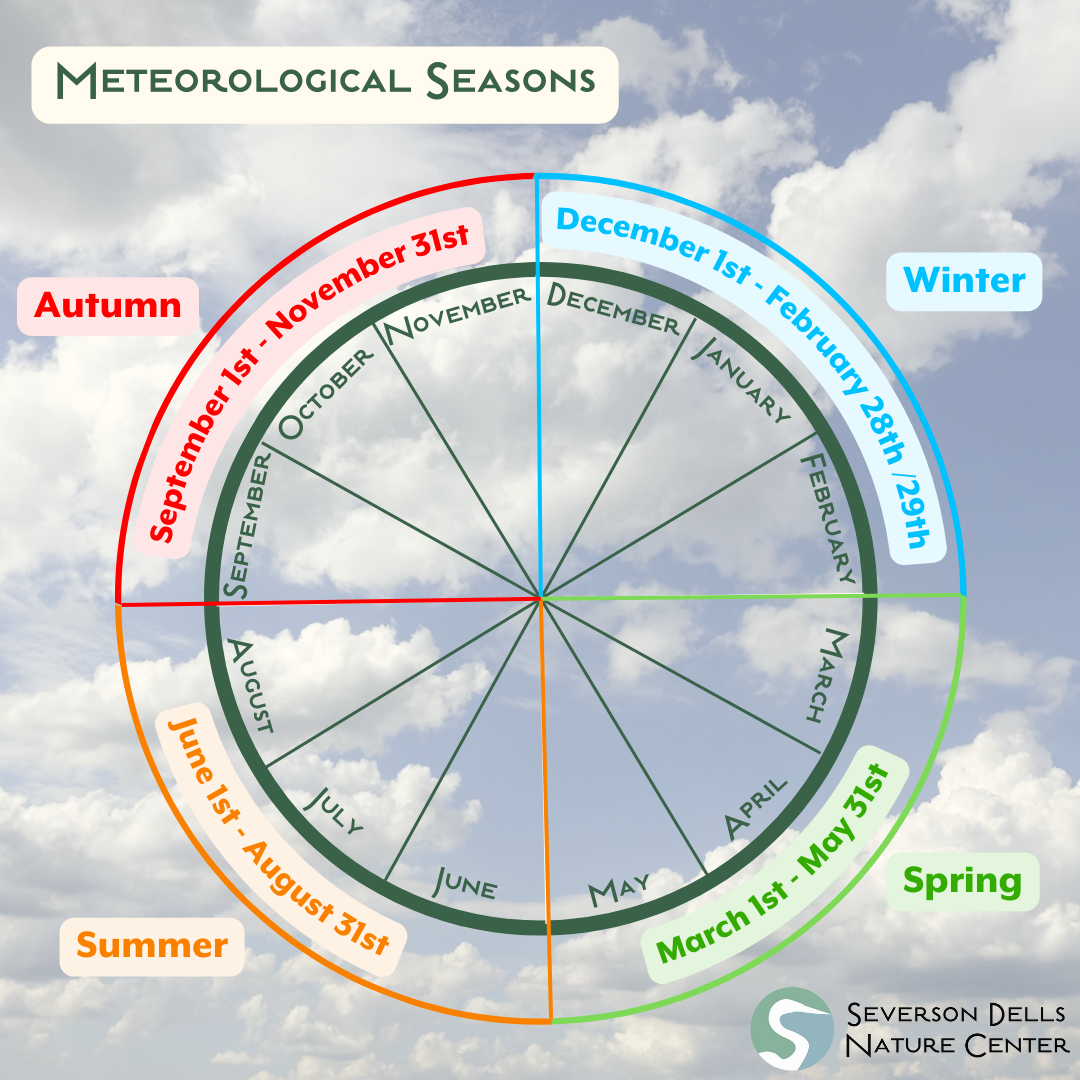

Meteorological seasons (think meteorology; forecasting weather) are grouped together in three-month blocks based on average temperatures. Instead of including only the last ten-ish days of December in the official definition of winter like the astronomical method would, meteorological winter includes all of December, January, and February, since those tend to be the coldest months of the year.

This way of classifying seasons is much easier to work with when predicting things like weather and crop schedules because there is less year-to-year variation in the length of seasons. The length of seasons always stays the same, with the only exception being leap years , when winter is one day longer. Meteorological seasons also match better with our standard calendar since it’s able to be broken down into full months, allowing us to say things like, “students don’t have classes in the summer” instead of, “students don’t have classes during the last third of spring and the first two-thirds of summer.” That would be quite the mouthful!

Using the meteorological definition, each season begins on the first of the month.

Additionally, meteorological seasons surround the solstice and equinox, including some time before those astronomically significant days and some time after them. So while the astronomical seasons would consider the warm days of mid-June to be spring (because the summer solstice doesn’t occur until around June 20th), the meteorological seasons recognize all of June as a summer month because it has some of the warmest yearly temperatures.

Both of these ways of defining seasons have value, which is why we keep them both around! For the average person, the meteorological seasons are more comprehensible because they follow the calendar that we are familiar with and are distinguished by something we all experience: temperature. Astronomical seasons, on the other hand, give an important context for why our temperatures vary throughout the year the way they do. Most ancient calendars were based on the astronomical seasons because there were clear and measurable events (namely the solstices and equinoxes) that signaled the change of seasons.

Whether you want to use the meteorological definition or the astronomical definition of spring, we still have a few weeks of winter before we should start expecting warmer temperatures and ephemeral flowers popping up. So instead of spending our time longing for the green leaves of spring, let’s choose to take advantage of the short-lived beauty of snow lining the trees! There are plenty of ways to stay active and connected to nature, even when it’s cold. Be sure to check out our events calendar to see how you can stay connected to people and nature this winter!

RECENT ARTICLES