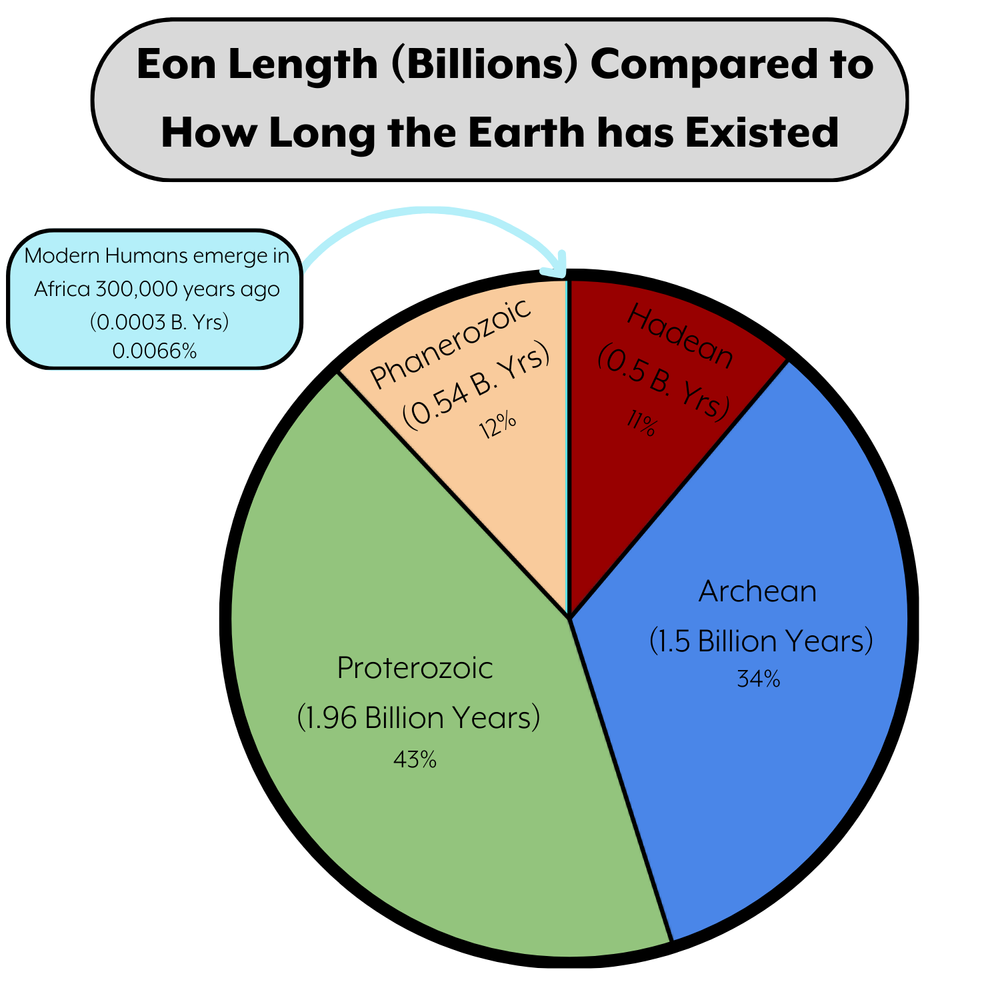

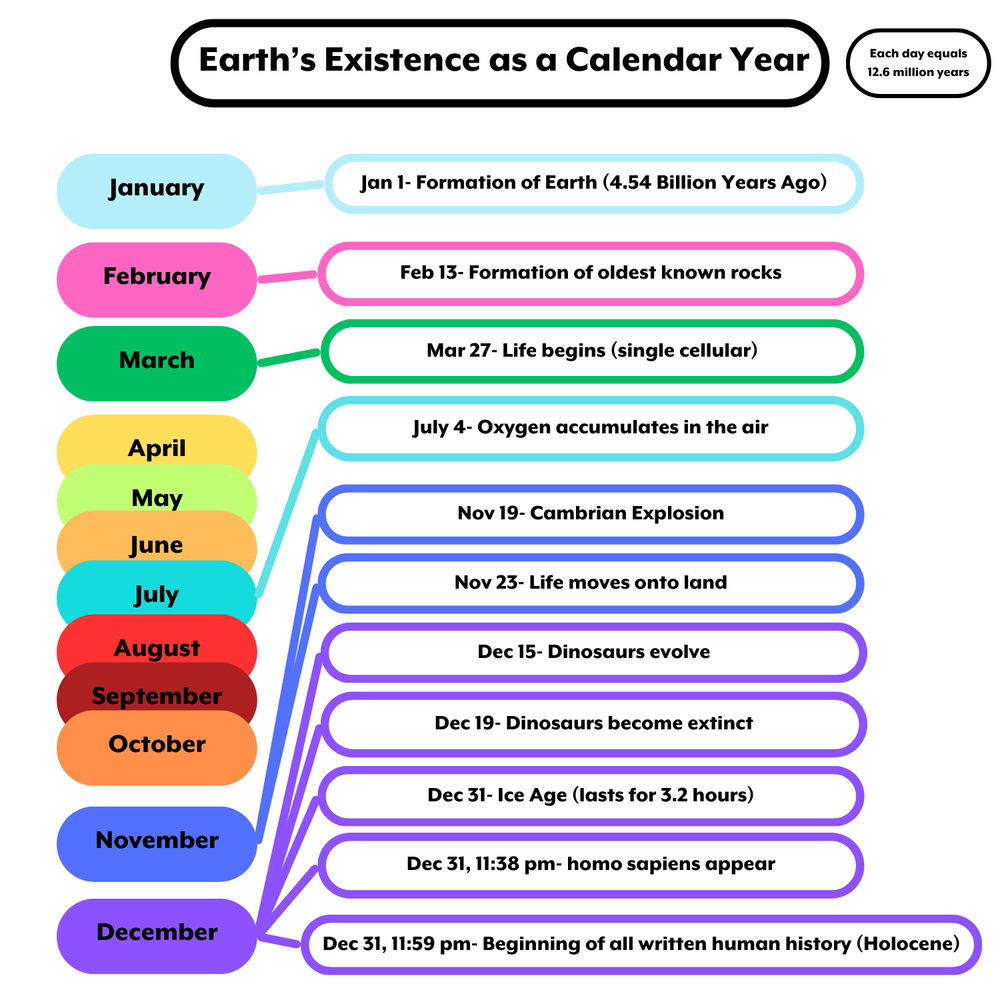

The Eons of Earth are long and diverse, I’ll be showing some of the unique events happening in each eon and try to explain where Severson would be in this time period. The image to the right shows how long each Eon is in compared to how long the Earth has been a part of this universe. If you look extra closely you can see the tiny little sliver of light blue where the modern humans first came into existence showing truly how our time on this planet has been infinitesimally small so far.

FIELD NOTES BLOG

Severson Through Billions of Years

How Old is the Earth?

The Earth is extremely, unimaginably old- even now it's hard for me to truly comprehend given I have only been around this planet for a very short amount of time (25 years give or take a few). On the contrary the Earth is about 4.543 billion years old (± 0.05 billion years). That means the Earth is almost two hundred million times older than me, but to be honest that still barely makes any sense, so let's try to rectify that. From there we will develop a better understanding of each of the different eons that exist and view where Severson Dells might be in this situation.

Visualizing Absurdly Large Numbers

There are a couple ways to visualize big numbers. Let's start off with the ‘smaller’ number of 1 million. If you were able to count one number per second without stopping (a herculean feat that is impossible for a human but oh well). It would take 11 days, 13 hours, 46 minutes, and 40 seconds to count from 1 to 1,000,000. So that is with optimal conditions. Someone has actually counted to the number 1,000,000 and it was recorded all online for the history books. His name is Jeremy Harper and he counted to one million to raise money for charity (Jeremy Harper Counting). Averaging about 16 hours a day it took him 89 days to count from one to one million. Now let's look at that pesky billion number. There are a thousand millions in a billion, so with optimal conditions of one number a second it would take about 32 YEARS to count to one billion. If you were as dedicated as Jeremy Harper (who might I remind you spent 16 hours A DAY counting) it would only take you 243 YEARS to count to one billion…. Then just do that 4 and a half more times to get to the age of the earth at a simple 1103 years of counting non stop for 16 hours a day.

How do we know how old the Earth is?

There are a lot of techniques that people have used to determine the age of the Earth (some more unreliable than others but all similarly fascinating). One of the more consistent ways to determine the age of something is looking at some isotopes of radioactive elements because they decay over time at a predictable rate. This means we can calculate how old certain rocks are by measuring this rate of decay. The issue is rocks go through a process called the rock cycle which is the method of transformation from one type of rock to another, so there likely are not any rocks that still exist in their original form from the first moment on the Earth. The oldest minerals found on Earth were found in Western Australia and these little Zircon are measured to be as old as 4.404 billion years old. This tells us the Earth is at least 4.4 billion years old but for more information we need to look elsewhere away from Earth itself. Other aspects of our solar system likely formed at the same time as the Earth itself. The moon has rocks as old as 4.5 billion years old and there have been asteroids that have ages that range between 4.4 and 4.5 billion years. These are more clues that aid in confirming this theory of earth being 4.54 billion years old (± 0.05 billion years). Now, lets visualize how old that really is. If you shrank down the 4.54 billion years old that the Earth is into a single calendar year there are a lot of things that are happening in that year but lets just focus on some special ‘holidays’.

Eons of Earth

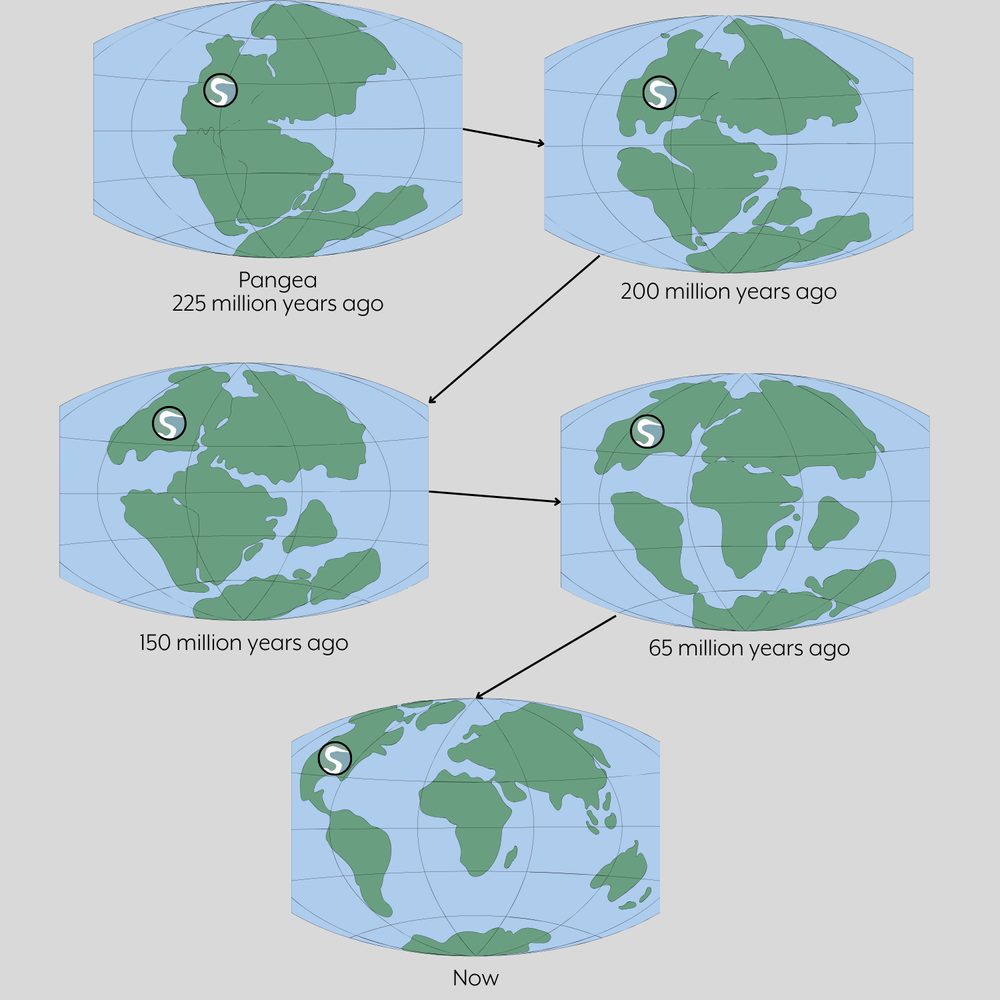

Severson's Timeline

Utilize the graphic below to travel through the timeline of Severson...Click on the 'Eon' listed to learn more!

RECENT ARTICLES