FIELD NOTES BLOG

Ocean Currents and our Changing Climate

Having lived in the Midwest for my entire life, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the ocean. Sure, I appreciate the beauty of the coral reefs and kelp forests as much as the next person, but I have never felt a strong connection to marine environments. What I do feel a strong connection with, however, is the climate crisis and the future of our ecosystems. I’ve recently been ‘diving’ (pun intended) more into the role our oceans play in regulating the climate, and it has spurred a new appreciation in me for the world’s waters.

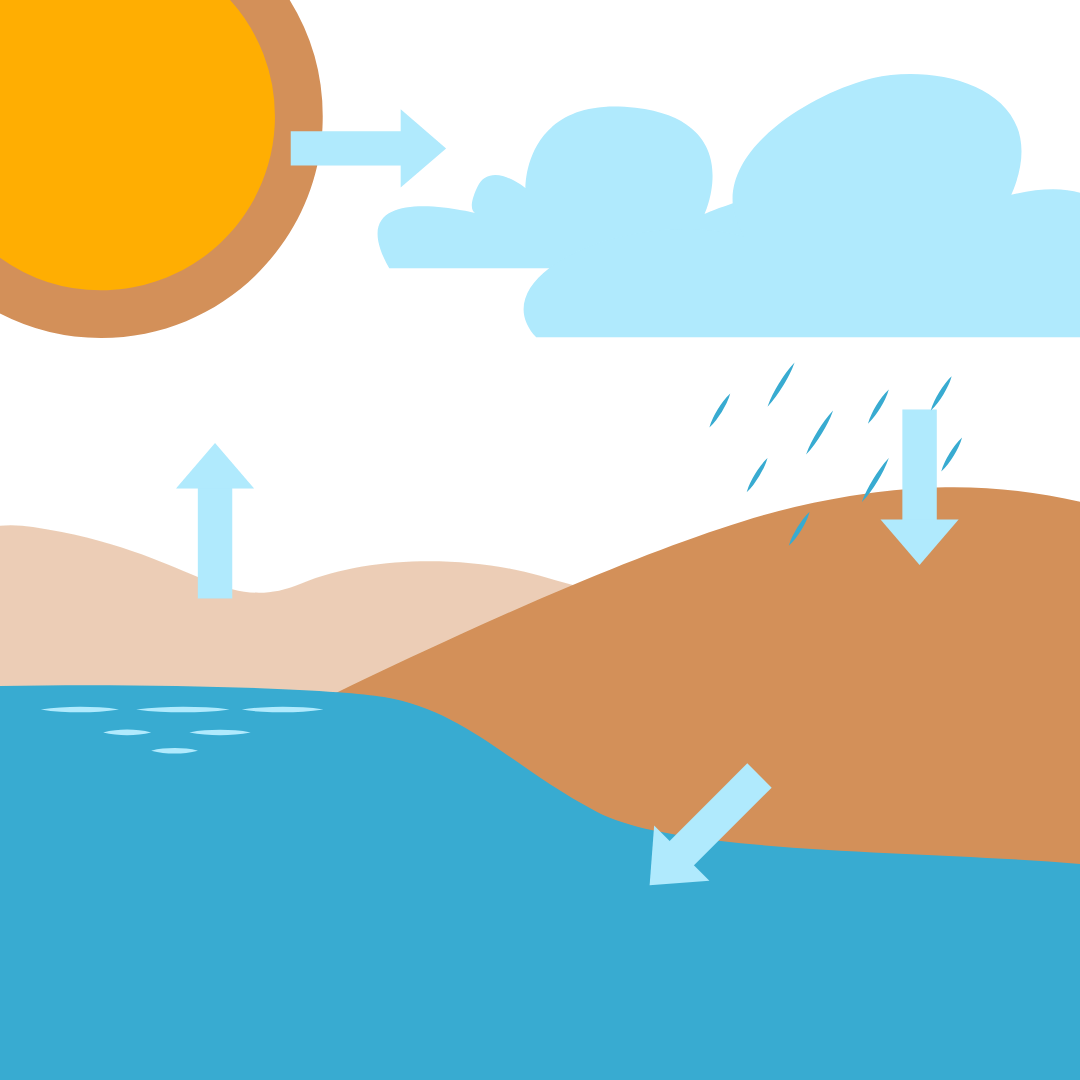

The water cycle. Sunlight heats surface water and allows it to evaporate. Then it will condense into clouds and precipitate back to the surface.

Water, in general, is great at absorbing and retaining heat. Think about those cold mornings where steam rises from a lake or river: this is because the water is holding more heat than the air. On an ocean-level scale, water absorbs most of the heat that enters our atmosphere from the sun, and this drives the water cycle. For those of us who haven’t thought about the water cycle since fifth grade, it’s just the movement of water around the world as it changes between solid ice, liquid water, and gaseous vapor. The water cycle allows us to treat water as a renewable resource, even though we never really create “new” water.

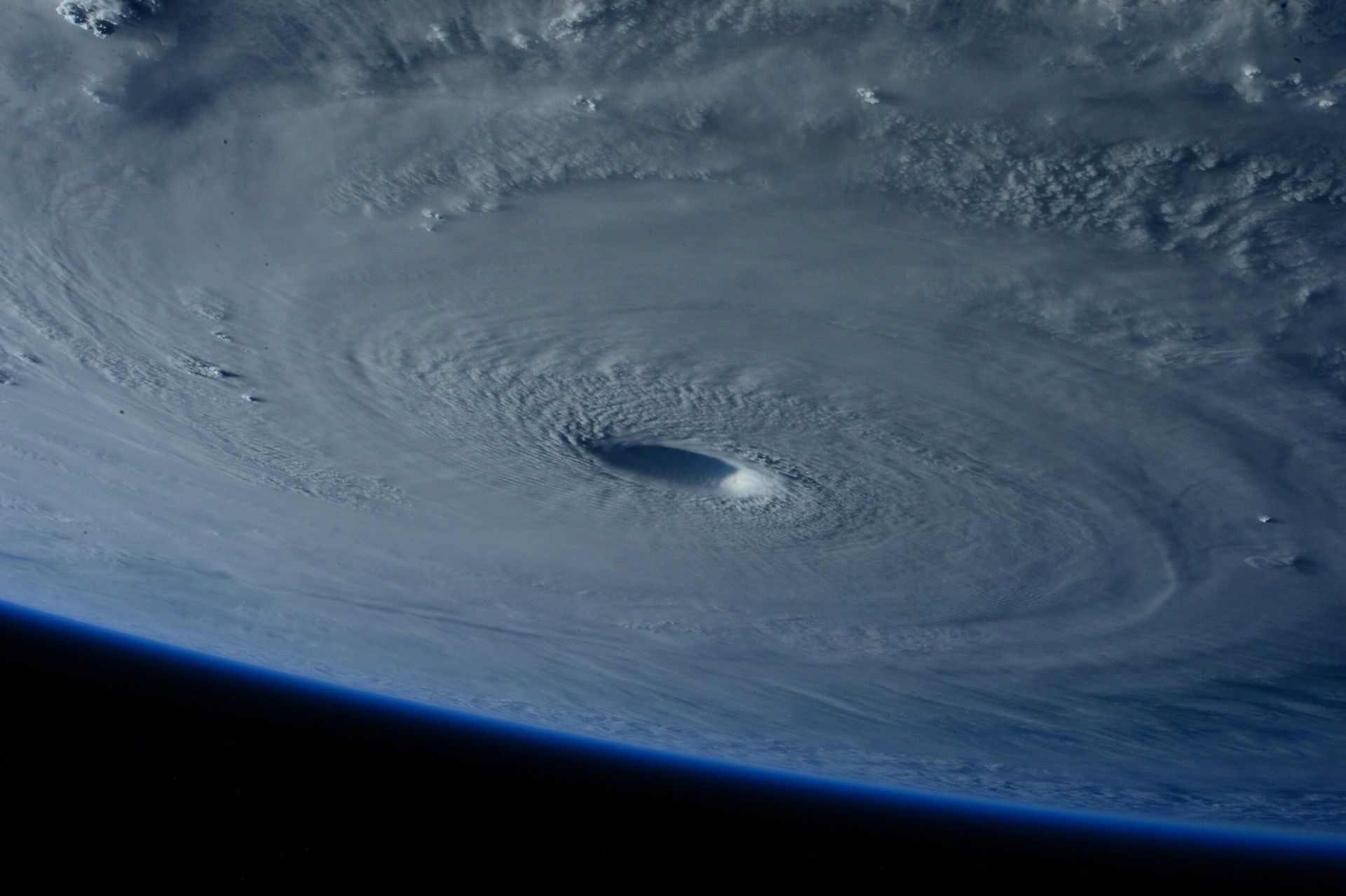

As global temperatures rise, the ocean tries to compensate for the warmer atmospheric temperatures by absorbing more heat energy. In turn, ocean temperatures rise and rates of evaporation increase. With more water vapor in the atmosphere, storms can generate more often and with a higher severity. For example, in 2023, for the first time in recorded history, a Category 5 tropical cyclone was documented in all 7 tropical storm basins around the world. This means each area experienced at least one hurricane, typhoon, or cyclone with sustained winds of at least 157 miles per hour !

A tropical cyclone, seen from space. Photo from NASA.

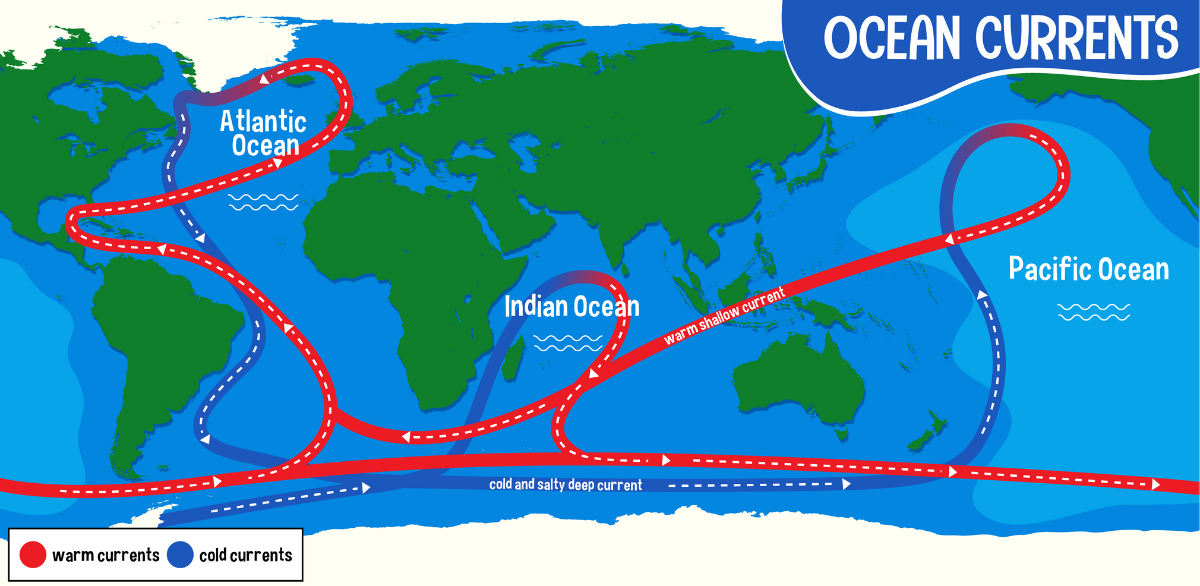

Beyond the effects on the water cycle, climate change has been impacting ocean currents as well. Ocean currents distribute heat energy from the tropics towards the poles and moderate temperatures in the process. For example, Paris, France is actually farther north than Fargo, North Dakota, but because the west coast of Europe sits along a warm ocean current, the climate is much milder in Paris.

Many factors drive the strength and direction of ocean currents, including winds, tides, water salinity (saltiness) and density, and solar heat. You can think about global currents as a conveyor belt that wraps around the oceans and pushes or pulls water in a pretty consistent direction depending on a combination of these factors.

To help us understand this, let’s imagine that we are a drop of water making our way through the global ocean current . We’ll start in the North Atlantic off the coast of Greenland, surrounded by sea ice and glaciers. We don’t have a lot of heat energy because of the cold polar temperatures, and the sea water seems unusually salty. Since salt water leaves behind its salt when it freezes, all the sea ice around us has left the water extra salty. This combination of cold temperatures and extra salt is making us more dense than other surface water would be, so we sink from the surface into the deep ocean currents. When other surface water flows in to take our place, the cycle begins.

The ‘Conveyor belt’ of global ocean currents. Cold, salty water sinks near the poles, which powers the current to distribute heat and nutrients around the world.

We can stay in this deep ocean current for a long time (deep ocean currents only flow a few centimeters every second ), following the topography of the sea floor south towards Antarctica. Since we are so deep, tides and winds don’t have a huge impact on us anymore, so we just keep flowing south! Near the coast of Antarctica, we will be “recharged” with more cold and salty water as the same process occurs for the southern hemisphere.

Now, our deep current splits into two: one that flows along the eastern coast of Africa towards the Indian Ocean, and another that flows through the western Pacific Ocean around the eastern coast of Australia and Asia. Regardless of which current we travel on, we will soon make our way back to the ocean surface through a process called upwelling. When strong winds blow surface water away from an area, the deep ocean water flows in to fill that space.

Calm ocean water. Photo by Thomas Vimare.

Now that we are back on the surface, we can be warmed by solar energy again, which makes us slightly less dense and helps keep us up on the surface. From here, winds and tides will push and pull the currents around the globe until, eventually, we reach the cold water near the poles and the cycle starts again. In total, it can take upwards of 1,000 years for water to complete a trip around the global ocean current conveyor belt.

When we factor in warming global temperatures to our ocean current, researchers have come to the alarming conclusion that the global conveyor belt be slowed or stopped due to climate change . As warmer temperatures cause sea ice at the poles to melt, the surface water won’t be as salty, making it more difficult for that water to sink and pull water into the deep ocean currents. Since this is the first step of the global current, it would throw off the whole cycle. Not only would warm surface water be more likely to remain in the tropics (goodbye mild Paris climate!), but the cold, nutrient rich water from the poles that supports the global marine food chain would be less likely to flow around the world, disrupting marine ecosystems and the human economies that depend on them.

The moral of the story: even if we in Illinois won’t necessarily feel the impacts of climate change in the form of sea-level rise, we still depend on the ocean for regulating our climate. Melting sea ice and glaciers will add more freshwater to the ocean that has the potential to disrupt the global circulation of water and heat, which impacts everyone, regardless of where on the planet you live. Being far from a coast, it’s easy to forget all the benefits we enjoy from the oceans, so it’s important that we take the time to understand and appreciate how connected we still are to this global force. Thanks oceans!